- Home

- Tracey Iceton

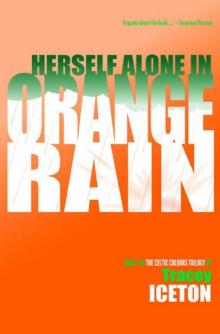

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Page 10

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Page 10

‘We should go, John, before Kaylynn gets injured.’

‘Don’t worry, Susan, she’ll be fine. They wouldn’t dare.’

‘But what if…?’

‘No. We need to stay, show we won’t be bullied by self-serving bureaucrats and state-paid thugs.’ …

We were always caught in the current, swimming outside the flags.

Today I didn’t even go paddling.

I start tiptoeing through the debris, sidestepping bloody puddles.

Ahead an old man struggles to his feet. I think of Daideo, his final frail form, and rush to help.

‘Thanks, love,’ he says, turning a bruised face to me. ‘Are you hurt?’

‘I’m fine. Let me get you someone.’

Before I can go for help a reporter charges us, a young woman with a neat bob, wearing a tan mac and court shoes and towing a cameraman.

‘Can you tell us what happened?’ she asks.

‘Aye, them bastards baton charged us. It was Bloody Sunday all over.’

She pounces on his words, thinking she has the scoop. ‘Was there shooting?’

‘Ach, I don’t mean that business in Derry. I’m talking 1913. The Lockout. My grandda was on the strike. He was only thirty-five but he was made an ould man in one afternoon. Walked with a limp the rest of his life after them buggers broke his leg. He made sure us children knew the horror of it. They’re not the DMP anymore but they’re the same shites they always were.’

She sags with disappointment. ‘What about today?’

‘They battered us. Thugs they are. Don’t give a damn who they’re beating so long as they keep the Brits safe.’ He spits bloody phlegm onto the pavement. ‘I saw a woman kicked to the ground. They kept hitting her even when she was down.’

The reporter scribbles in her notebook. Turns to me. ‘Did you see that?’

‘I’ve just come.’

‘Oh.’ She refocuses on the old man. ‘What else can you tell me?’

I drift away.

I don’t know how long I’ve been walking but it’s dark when I realise I’m leaning over the railings, staring into the Liffey’s dank waters. I ache with cold, am stiff when I straighten up. I turn from the river and head onto O’Connell Street. I’ll sign Martin’s book. It’s nearly nothing but it’s the only thing I can think to do.

O’Connell Street is quiet. A candlelit gathering clusters outside the GPO. I trudge towards the makeshift camp of trestle table, deck chairs and sleeping bags. A purposefully gaunt young man, one of the sympathy strikers I guess, greets me.

‘How’re you?’

‘I’ve come to sign the book.’

‘Grand.’

He leads me to the table. Hands me a pen. I’ve no idea what to write. I scrawl one word: sorry. Put the pen down.

‘Did you see the trouble today?’ he asks.

I’m fumbling for an answer when a gardai patrol peels into the street, sirens screaming. Dozens of men spring from the vans and charge us, yelling, ‘Disperse, disperse.’ We’re plunged into a seething storm of batons and shields. I’m shoved against the table, hauled off it and tossed aside. The book is snatched up. A garda rips it apart, scatting the pages. The table is overturned.

‘Oi, you can’t…’ The young man steps forward.

The peeler rounds on him, whacks his arm with a sickening crunch that I feel in my bones. The lad yelps, staggers back. The garda hits him again, knocks him over, kicks him. Raises his baton. Brings it down on his leg. The lad howls, an animal cry that suffocates me. The peeler hits him again. The leg snaps with a dry, hard crack. The pain of it paralyses me. I can’t move. The peeler winds up for another blow. The mob swells around me. A thick blue line obscures my view. I’m bundled backwards, feet floundering. I right myself, turn. Run.

Dublin—19th July, 1981

Violence Erupts Outside British Embassy

Approximately 200 people required hospital treatment after a demonstration supporting the hunger strikes turned violent yesterday following attempts by the Free State gardai to block the route.

The march, organised by the National H-Blocks/Armagh Committee who have a strict policy of peaceful protest, began in an orderly manner in the centre of Dublin. As the 15,000 marchers neared the British Embassy they encountered around 1,000 gardai, assembled to protect the embassy building.

The gardai, armed with batons and shields and dressed in riot gear, prevented protestors from nearing the embassy, forming ranks twelve deep outside the building. Protestors attempting to disperse found roads blocked by barricades. Frustrated, a small minority of demonstrators began throwing stones towards the gardai lines. The gardai responded with a brutal and sustained baton charge, indiscriminately attacking innocent protestors, journalists and foreign visitors. One man described seeing a woman kicked to the ground and others reported unconscious victims being beaten. Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald said, ‘What was done was the minimum necessary to protect the situation.’

Later, in an unprovoked attack, around a hundred gardai destroyed the book of condolences for Martin Hurson and viciously beat those who had been keeping a peaceful vigil outside the GPO. One man suffered a broken arm and leg.

Sinn Fein has called for an enquiry into the brutal actions of Free State forces which saw many innocent bystanders seriously wounded.

I sit with Daideo’s boyhood passport on my lap, flipping between the cover with its crest of a free, united nation, and the first page where his real name, William Devoy, is written. Renaming is a family tradition.

The procedure is more complicated these days, there’s paperwork, signatures are required but a fortnight later I have an Irish passport in the name of Caoilainn Devoy. Kaylynn Ryan’s British one still has nine valid years. Calculating its possible value, I stow it for future use.

My choice is made.

‘Ah, Jesus,’ Aiden says.

We’re in my sitting room, fish and chip papers littering the coffee table, the ashtray filling up with dog-ends. I’ve just told him I want to join the IRA.

He rubs his scar. ‘What about Sinn Fein? If you’re wanting to help that’s...’

‘Not enough. I won’t spend time on picket lines when there are battle lines need manning.’

‘You can’t.’

‘Don’t the ’Ra take women?’

‘Sure, they do but... you don’t know what you’re getting into.’

‘I’ve a good idea from looking at the state of you,’ I snap. His expression darkens. It’s reason, not rage, that’ll convince him. ‘I’ve been watching and listening: learning. I’ve asked myself every question, over and over until I’m sure of the answers. But ask me again, now, if you’re needing to hear for yourself.’

He hesitates.

‘Go on, ask me!’

‘Why this, why now?’

I can’t tell him I was at the GPO, ran away when I should’ve fought.

‘I don’t want to be powerless anymore, like those poor sods clubbed outside the embassy.’

‘Jesus, Caoilainn, you shouldn’t do this because of that.’

‘I’m not. That’s just what made me see military action is the only way.’

He shakes his head. ‘It’s a rough life; on the run, in hiding, half your time bored to death, the other half scared to death. Can you handle that?’

‘I won’t know until I try but, yes, I think so.’

‘What about if you get caught? Jail?’

‘I’ll survive, just like every other volunteer.’

He bites his lip, chewing on the indigestible question that I know comes next.

‘Are you ready to die for this?’

‘No one’s ready for that. If they think so they’re deluded. Yes, it could happen. I accept it. But I’ll do my damnedest to prevent it.’

‘Jesus, Caoilainn. You can’t do this.’

His intransigence shatters all rational arguments. I lash out.

‘Aren’t my Republican credentials good enough?’

/> ‘Is that what this is about? ’Cos that’s the wrong reason.’

‘It’s fine for you to be ‘Republican in your bones’ but not me?’

‘That’s different.’

‘How?’

‘It just is.’

‘Because I don’t live on the Falls? Because I’ve not a brother dying in jail? Because I’m a woman?’ I turn away, fight for control before it’s beyond me.

Silence simmers.

He sighs. ‘It’ll be harder on you, so it will.’

‘I’m not expecting it to be easy. Women always have to work harder than men to draw level with them. That’s what makes us better survivors: fighters. Just because someone says you can’t do something doesn’t mean you shouldn’t still try. You should know that; it’s why you’ve been fighting. I’ll do whatever it takes.’

He pulls me round to face him, raises his eyes to mine. ‘Even if that means pulling the trigger? You need to understand what a hard thing that is, even if they are the enemy. You’ve to live with it and you can only do that if you believe, absolutely, that it’s the only way.’

‘I know. I’ve thought about all this, been thinking for weeks, months.’ I hand him my new Irish passport. Aiden opens it, reads the name. ‘I’ve made my choice.’

Aiden arranges for us to call on Martin. This time there’s no pounding heart, no panting lungs. I know what I’m here for and I’m ready. There’s no tea and biscuits either, this time. Martin sits us in the lounge and opens with a challenge.

‘So you’re after joining the ’Ra.’

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘Same reason as you.’

‘You saw peelers kicking shite out of women and kids marching peacefully for their rights, getting their skulls caved in by a Paisleyite mob with clubs?’

‘No, but I saw what the Gardai did in Dublin.’

He raises his eyebrows. ‘Oh, aye?’

‘It’s wrong and I don’t see any other way of making it right, here or in the north. If something’s not fair you fight it. That’s how Daideo taught me to think. And I don’t mean fighting with banners and petitions,’ I add in case he tries fobbing me off with Sinn Fein.

‘Sure, your granddaddy was a tough ould fella, but that raises another question. I’ve to ask myself if that’s what’s bringing you here: family history.’

‘Is that a problem?’

‘If you’re fighting a war that’s not yours, then, aye.’

‘I’ve as much right to it as anyone, maybe more. I’ve been involved in this since before I was born. Of course that’s what’s brought me here. But the past’s only half the reason.’

‘The other half?’

‘There’s an occupying army in the north, who’ve no right being there, supporting a bunch of bigoted overlords who don’t care about anything but themselves. If we want what’s fair we have to make it happen. I think the way to do that, right now, is to fight. The Brits are the ones who brought out the guns. They started it. I want to help end it. So our reasons are the same,’ I add. ‘An end to injustice in Ireland.’

‘Fair play to you,’ Martin says. ‘You’ll need to believe that if you’re to see this through.’

‘I do and I understand the dangers. I’ve already heard the ‘Jail or Cemetery’ speech.’ I look at Aiden who flushes.

Martin grins. ‘Alright, but we don’t just give you a gun and send you off. You’ll have to be vetted, trained.’ He takes what looks like a small school exercise book from the sideboard and drops it in my lap. ‘Start with that.’

The cover is a dry, plain green, the pages stapled together through the middle. I thumb through. A heading catches my eye: Guerrilla Strategy.

‘What’s this?’

‘The Green Book: your new Bible,’ Martin replies. ‘No one joins ’til they’ve studied that. Read it then tell me you’re still keen.’

The Green Book is a mix of political philosophy and ‘how to’. Western individualistic capitalism and Eastern state capitalism are criticised equally for their inability to provide for and protect the people. To me it’s familiar rhetoric with a new colour-scheme: the green of Irish nationalism. It covers eight hundred years of Irish conflict, justifies military action, explains the IRA are the legitimate representatives of the Irish people and outlines the fivefold strategy for guerrilla warfare. There are two objectives: long term, Democratic Socialist Republic of Ireland; short term, Brits out. The truth is brutal; the understatement blackly humorous: Volunteers are trained to kill…before any person decides to join the Army he should think seriously about the whole thing.

She has.

When I’ve finished reading, I dial the number given me. The next day a girl in a green blazer and white knee socks rings my bell, hands me an envelope and darts away to school. The note states a time, date and a Dublin address. I’m getting Green Booked in three days.

The address is a florist’s. I wander in the afternoon before my appointment? interview? induction? and choose a modest spray. Behind the counter is a middle aged woman in an overall. She counts my coins then rings them into the till.

‘Do you want a card?’

I test out the accent I’ve been practising. ‘No, thanks. You haven’t a loo I can use, though, have you? I’ve been caught out by a wee visitor.’

She gives me a motherly smile and points to the door behind her.

I dart through, climb the stairs and open each of the four doors on the landing, the excuse poised on my tongue. There’s a bathroom, sitting room and two bedrooms, beds neatly made with candlewick bedspreads, one pink, the other blue. A picture of the sacred heart hangs in one. The only way out is down the stairs.

Satisfied, I thank the florist and leave.

I’m there two hours before the stated time. Sitting across the street in a bus stop, I’ve an inconspicuous view of the shop. One at a time, four men appear and enter. One of them wears a combat jacket, the others are in suits, jeans, jackets. From his graceful stride I identify one of them as Martin.

When it’s time, I hitch my rucksack onto my shoulder, cross the road and knock. Martin opens the door.

‘How are you?’

‘Grand, yourself?’

He nods. ‘This way.’

I follow his tall shadow, smiling at the knowledge that I could have led him.

On the landing is the lad in Army gear but with the addition of a balaclava he wasn’t wearing when he came along the street. Martin stops.

‘We’re needing to search you before we go in.’

I hand over my bag and lift my arms. The Army lad looks to Martin, his eyes widening, the whites visible through the eyeholes.

‘Come on, sunshine, we’ve not got all night,’ Martin barks.

The lad pats me down with the trembling hands of a good Catholic boy. If I had half a pound of gelignite in my bra he’d never have found it. I make myself stand motionless, aware it’s me being tested, not him.

Search over, Martin opens the sitting room door. Three straight-backed chairs form a semi-circle around a fourth. Martin takes the middle seat of the three. Either side of him, the two others sit eyeballing me. One is stocky, a square face, thick brows over brooding eyes, an unsmiling mouth and a dimpled chin. The other is leaner, a beard guarding plump lips and glasses framing eyes that penetrate.

Martin indicates the waiting chair. ‘Have yourself a seat.’ He clasps his hands on his lap. ‘Tell us why you want to join the Republican Movement.’

‘It’s the only way.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I can’t see anything else making a difference.’

‘You don’t believe in politics?’ asks the one with the glasses.

Obviously he does.

I was ten. We were racing to London in a Morris Traveller that rattled and squealed. I was reading The Famous Five: Five Get Into Trouble. They were planning the protest for freeing the Pentonville Five…

‘It’s outrageous, John. They’ve

no right jailing people for picketing.’

‘But they have, thanks to this bloody new Industrial Relations Act. You see, Susan, what happens when you put faith in politicians. They screw you over for their own ends. It’s always the same; give them power and they abuse it.’

‘If you can’t trust politicians, Daddy, why do you and Mummy vote?’

‘To remind the bastards they owe you, Kaylynn.’

‘John, don’t tell her that. Love, we vote because it’s all our responsibilities to exercise the rights we’ve got. But that doesn’t mean we should trust politicians and governments to protect those rights.’…

‘I don’t believe in politicians,’ I reply. Mr Politics frowns. I add, ‘I do believe in doing what needs to be done. Right now, to me, that’s fighting. When, if, it becomes voting I’ll do that too. But I’ve been to Belfast and it’s not there, not yet.’

Martin smiles tightly. ‘And that’s what you want, to make a difference?’

‘Yes.’

‘Even if doing so means killing, being killed?’ demands Mr Politics.

All people wishing to join the Army must fully realise that when life is being taken, that very well could mean your own.

‘Yes,’ I say hotly, ‘and I’ve read your wee book so I’m clued up.’

Mr Politics tuts. Martin and the other man exchange raised-eyebrow glances. I choke down mushrooming irritation, rinse my words with cooler water.

‘I’m totally clear what this course of action entails. I wouldn’t dare come if I wasn’t.’

There’s some nodding. Politics strokes his beard.

The third man takes his turn. ‘You’re the wee girl who painted the Sands mural.’

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain