- Home

- Tracey Iceton

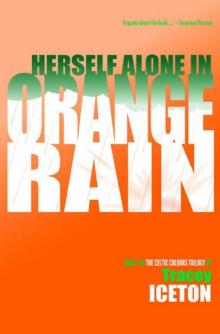

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Contents

Title

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Epigraph

Dublin—8th March, 1966

Plymouth—14th October, 1980

Dublin—15th October, 1980

Dublin—18th December, 1980

Belfast—26th December, 1980

Dublin—1st March, 1981

Belfast—7th May, 1981

Dublin—13th July, 1981

Dublin—19th July, 1981

Belfast—9th August, 1981

Belfast—3rd October, 1981

Belfast—23rd December, 1981

Belfast—9th January, 1982

London—27th April, 1982

London—20th July, 1982

Loughrea, Co. Galway—20th September, 1982

Loughrea, Co. Galway—23rd September, 1982

County Antrim—25th September, 1983

Coalisland, Co. Tyrone—4th December, 1983

London—13th December, 1983

London—17th December, 1983

Brighton—15th September, 1984

Belfast—12th October, 1984

Belfast—4th December, 1984

Castlereagh Interrogation Centre—12th December, 1984

London—14th December, 1984

Armagh Jail—25th December, 1984

Newcastle, Co. Down—26th December, 1984

Belfast—18th January, 1985

London—25th June, 1985

Armagh Jail—30th June, 1985

Armagh Jail—23rd September, 1986

Armagh Jail—29th September, 1986

Mourne House, Maghaberry Jail—30th September, 1986

Outside Maghaberry Jail—18th March, 1987

Galway City—27th April, 1987

Dublin—10th May, 1987

Ballygawley, Co. Tyrone—12th July, 1987

County Tyrone—25th July, 1987

Dublin—18th August, 1987

Ballygawley, Co. Tyrone—28th August, 1987

Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh—9th November, 1987

Ballygawley—18th November, 1987

Madrid, Spain—1st March, 1988

London—7th March, 1988

Dublin—8th March, 1988

Belfast—17th March, 1988

London—20th March, 1988

Belfast—20th March, 1988

Monaghan—22nd March, 1988 (morning)

Ballygawley—22nd March, 1988 (evening)

Dublin—3rd April, 1988 (Easter Sunday)

Ballygawley—15th April, 1988

Ballygawley—14th October, 1988

Belfast—4th May, 1989

Killed by The Troubles

Further Reading

Notes

HERSELF ALONE IN

ORANGE RAIN

TRACEY ICETON

Published by Cinnamon Press

Meirion House,

Tanygrisiau,

Blaenau Ffestiniog

Gwynedd

LL41 3SU

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Tracey Iceton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2017 Tracey Iceton.

ISBN 978-1-78864-028-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset in Garamond by Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Adam Craig © Adam Craig.

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress and by the Welsh Books Council in Wales.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the Welsh Books Council.

This book owes its existence to the following people:

Principally to Prof. Michael Green and Dr Fiona Shaw of Northumbria University without whose input this novel would be a pale shadow of the work it became under their expert guidance and insightful feedback. Jan Fortune at Cinnamon, who continues to keep faith with my Celtic Colours trilogy, and who unquestioningly embraced my blending of fact and fiction in this novel, enabling me to tell the story as I felt it had to be told. Danny Morrison who kindly took the time to discuss the premise of this novel with me and who offered suggestions that shaped the plot as well as continuing to support my writing. Jim McIlmurray for welcoming me in to view his unique collection of Troubles memorabilia, for recounting his experiences of the Troubles and for the useful contacts he helped me reach out to.

Maírtín Ó Meachair of Teach an Phiarsaigh (Pearse’s Cottage) in Rosmuc, Galway who was kind and generous enough to, again, correct my use of Irish throughout the novel. Hilary Bryans who worked as a journalist in Northern Ireland during the 1980s and kindly shared her memories of life there during that difficult period with me, adding many authentic details to the book.

Fellow PGRs at Northumbria who provided feedback, encouragement and alcohol when needed, in particular Rowan, Jo, Jane, David and Jen. Also, all the staff in the English and Creative Writing department at Northumbria who supported me, helping me make the most of my post grad research opportunity and giving me the chance to develop and share my creative practice for this novel. To all those writers of works creative, critical and socio-political from whose texts I drew both information and inspiration during the research and writing process of the doctorate from which this novel emerged. David Willock who both proof read the novel and generously praised it for its portrayal of the futility of war.

Pen Pearson, poet and author of Bloomsbury’s Late Rose, who, having read the final draft of the novel, offered what I take to be the highest praise one author can give another when she said it was a book she wished she had written. John Dean, noted crime writer, who found the time to read the novel and who so generously offered a glowing endorsement of my work. Clare Wren who, besides reading the novel, supporting my writing and sharing her memories of the period with me, also made a vital contribution to the accuracy of my depiction of Catholic mass and wedding services. Without her input those scenes would have been woefully erroneous and greatly lacking in significance. Natalie Scott, whose long standing friendship and writer’s expertise were both essential to me during the arduous process of writing, redrafting and critiquing this novel for my doctoral thesis.

My family, both Johnsons and Icetons, who continue to unfailingly support my dream of being a writer. Thanks to them I can continue to live the dream. My husband, John, to whom I owe the greatest debt of thanks. For the three years it took me to develop this book he maintained a steady course, encouraging me to do the same, even when it felt like the ship would sink. His unconditional support of my writing is deserving of so much more than I can offer in these lines. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

And finally, to all those women and men whose Troubles tragedies are retold in these pages.

Unlike Green Dawn at St Enda’s, which was born in the emotive setting of Kilmainham Gaol’s execution yard, Herself Alone materialised when fellow writer Natalie Scott suggested I devote part two of my Celtic Colours Trilogy to exploring the war from a female combatant’s perspective. I wondered if this was possible, plausible. Did women fight for the Republican cause? And if so what was it like to be a woman in the IRA?

Research answered the first questio

n with an emphatic yes. There are twelve women on the IRA Roll of Honour; records of thirty-plus imprisoned for Republican activities. Official numbers are small but unconfirmed accounts report a 50-50 male/female attendance at IRA training camps,

And the second question? How would women volunteers think, act and feel while engaged in actions most cannot comprehend? What would bring them to the armed struggle? Were media portrayals of such women as the dupes of their male counterparts accurate? Some answers can be found in the few non-fiction books exploring the experiences of women freedom-fighters. I drew on these sources to create a character, but my protagonist is a fiction. This novel presents one possible account of what it might have been like to be a woman in the PIRA during the decade that encompassed the shooting of unarmed volunteer, Mairead Farrell, on Gibraltar.

In common with Green Dawn, Herself Alone also recounts real events, although far more recent, occurring between 1966-1988. Where facts were known I used them as accurately as possible within the scope of a fictional work. Where gaps existed I filled them with what I felt could have happened. Some events are entirely fictional. to greater or lesser degrees, from similar incidents, which did occur. Anything anachronistic is intentional and in response to the constraints of a fictional narrative. Real people feature here, but they are written as I imagined them from what I have learnt of their lives, transforming them into literary characters.

Unlike Green Dawn, Herself Alone is a telling, not a retelling, for the simple reason that, seemingly, no one has before dared to tell this story. That women do take up arms for their political ideologies is an undeniable truth. I hope in writing this novel I have gone some way towards communicating the lived experience of the women who gave up everything for their beliefs. They have too long been silenced by narratives content to portray them as victims or femme fatales. I offer such portrayals no quarter.

Tracey Iceton, 2017

‘Every woman gives her life for what she believes…

One life is all we have

and we live it as we believe in living it.

But to sacrifice what you are and to live without belief,

that is a fate more terrible than dying.’

Joan of Arc

Dublin—8th March, 1966

Explosion Destroys Nelson’s Pillar

Mixed Reaction as Imperial Monument Falls

An explosion on O’Connell Street has destroyed Nelson’s Pillar, causing minor damage to surrounding businesses. The incident, thought to be the work of Republicans, reduced the nineteenth century monument to rubble late last night.

No one was injured but falling masonry caused some damage, including crushing a parked taxi. The driver, Steve Maughan (19), escaped injury, having got out of the vehicle prior to the explosion. No group has yet claimed responsibility. The area has been cordoned off and will be inspected later by structural engineers.

The Pillar, erected in 1808 to commemorate the Battle of Trafalgar, has been the source of controversy, with many calling for its removal on practical, aesthetic and nationalist grounds. One local resident, Mr Patrick Finnighan (66), commented, ‘It was an insult to 1916.’

There is speculation that the IRA bombed the Pillar to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising, due to be commemorated next month.

The boys called to see me, making sure the ould fella was keeping well and letting me know the scéal.

‘Mr Finnighan, how are you?’

‘Grand. Yourself, Frank?’

‘Fine. How’s the wee ’un?’

A floorboard behind me creaked. It was herself, coming to investigate and wordlessly answer Frank’s question.

‘She’s such a fair thing,’ Frank crooned as she came to me, one soft fist clamped over the ould silver locket I let her wear, the other slipping into my leathery palm, sharp eyes seeing us and quick mind knowing us.

Caught in her gaze, Frank ruffled his hair in that frazzled gesture of his. Bursting to laugh, I watched the pair of ’em battle once again to get the measure of each other, certain Frank’d crack first, as always. And so he did, reaching into his pocket for the usual truce token, a lollipop.

She thanked him with the Irish I taught her, ‘Go raibh maith agat,’ put the lolly away for later and went to her room to play.

With her gone Frank set to telling me how they planned to commemorate the fiftieth. I thought it a grand idea. Decided I’d be there to watch and her wee self with me. See, I knew by then she was going soon. I had to pack her off with something more valuable than that useless silver trinket. Sure, she loved it, loathed to take it off, but it was worthless now, engraved with initials that had amounted to nothing. I needed a better bequest. Taking her to watch the boys at work was just the job, chance to show her that life’s a struggle, let her see the truth of what I’d been teaching her about fighting what’s not fair. I went to wet the tea. When I came back the tray shook in my dothery codger’s hands; the boys took it for ould age but ’twas the thrill of my secret plan, making me slop muddy pools onto the doily.

Three nights later I had her ready, muffled in winter boots and red duffle coat; the locket sat against the scarlet like a medal. As we stood in the hall, an odd pair, she clutched my hand, wondering, I bet, at the to-do. We shuffled out into the night as the hall clock chimed twelve.

She held my hand the whole way. As we closed in on the GPO I clung harder to her. I was afraid, in that darkness, of what was there, buried under a heap of time. I saw the bodies, heard the shots, felt the burning end of that unfair fight coming on me again. She musta sensed my fear, kept squeezing my twisted fingers with her mittened hand. I swallowed tears.

We tucked ourselves out of sight in Henry Street. Peering round the corner I saw Nelson, waiting on us, leering down. The eejit thought he’d seen us off in ’16. He should’ve known we’d be back. And so we were, me shivering in the shadows, the boys out there laying the charge. They knew what they were about sure enough but I didn’t much like the look of them in their Army clobber; heavy boots, blue jeans, dark jackets: balaclavas. I thought of what I’d worn: a kilt and a brat, pinned with a pierced sun brooch; a green uniform topped by a slouch hat; a fedora and trench coat, the length of it hiding a rifle. We’d no need of masks in my day.

The boys by the Pillar were set. I clocked Frank by that daft hair ruffling habit of his; even masked up he couldn’t stop hand from patting head. But then they got down to it, Frank pulling a sheet of paper from his pocket and reading it aloud. The night carried the words to me: the Proclamation. But it wasn’t the same as when I’d heard it read there before. The speech wasn’t his and your man’s words were too big for Frank’s mouth. Then they held a minute’s silence for fallen comrades, praying like the good wee Catholic boys they are. I bowed my head, thinking of poor Mick Collins, how we’d jigged in the street, ducking British bullets as we laid the charge, trying our damnedest to blow ould Nelson to hell. God and I never had any time for each other but Mick and me were solid, until the treaty.

At last one of them produced a lighter, sparked the flame. Rusted joints groaning, I crouched down to the wee ’un, pulling her in close.

‘Watch!’ I told her as he lit the fuse.

It burst like a star and fled into the blackness. We traced its flight, breath held. There was one almighty bang and one dazzling flash. I felt the sharp snap of shock fired through her, a gun’s recoil, but not a peep of fear passed her lips. The street lit up in furious orange; her green eyes shone, eager and alive. Down came the bollocks, in a rocky, rubbly rain. The boys cheered, punching their fists in the air. In our hidey-hole I murmured, ‘Éire go bráth!’ before turning us to the long walk home.

It was late when we got in. She’d said hardly a word. I put her to bed, tucking her in tight. One hand closed comfortingly over the locket, she stroked my crinkled cheek with the other.

‘Why did those men break that wee man, Daideo?’

‘Sure, it wasn’t fair, him being there, so they were doing so

mething about it. Like I’ve always told you to, Caoilainn.’

‘Was he a bad man?’

‘He was.’

‘Silly Daideo, he wasn’t real.’

‘I know, love, but you mind what I say: if things aren’t fair you fight ’til you make ’em fair. Do you understand?’

She puzzled it out a moment then nodded.

‘Good girl. Now to sleep with you.’

She curled up. I reached the door but she wasn’t done with me.

‘Why was Aidie’s daddy wearing a mask tonight, Daideo?’

Jesus, thinks I, she’s a smart one, clocking Frank like that.

‘Sometimes it’s better if people don’t know it’s you doing the fighting, love.’

‘Why?’

‘So they don’t try to stop you.’

She nodded again. ‘Are there lots of bad people?’

‘Some, but they won’t hurt you as long as you don’t let ’em. Remember that.’

I’d said my piece, too much of it maybe, but I couldn’t let her go without being sure she understood.

‘OK., Daideo. Can we go to the park again tomorrow and see the ducks?’

‘We can, unless it’s raining, then we’ll get the colouring books out, eh?’

‘Can Aidie come?’

‘We’ll ask his da.’

‘Aidie says if you feed them too much bread they explode.’

I cursed myself for letting her play so often with Frank’s youngest, little bugger, filling her head with nonsense when I had important lessons for her.

‘Does he now?’

‘Why do the ducks eat bread if it’s bad for them?’

‘Because no one’s told them they shouldn’t.’

‘That’s not fair, is it, Daideo?’

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain