- Home

- Tracey Iceton

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Page 2

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Page 2

‘I suppose not.’

‘Someone should tell them, like you tell me. That’s fairer. They’ll know not to be eating it. I’m going to tell them. I’ll tell the ducks they’re not to eat any more bread. I won’t let the ducks explode.’ She sat up, her wee angel’s face screwed down with the fight in her. I saw the past and the future in that look she gave off.

‘You do that, a chailín bhig.’ I kissed her goodnight. Left her lying in the darkness, planning a grand wee speech to the ducks. Aye, it was time she went.

Two days later the Free State army were in town to tidy up, demolishing what was left of the Pillar. That was the day the Ryans came to take what was left of me. It was best for her. She drove off with them, wrapped in her red coat, sucking the IRA lolly she’d saved for later.

Plymouth—14th October, 1980

I step back from the canvas, blinking eyes dry from straining over tiny brushstrokes, stretching shoulders cramped from fighting the whiteness of a painting in progress. Picking up my creased copy of the assignment brief I stare at the Plymouth School of Art and Design logo until it blurs then drag my eyes down to instructions I’ve read into memory but am still battling:

Family and Childhood

Explore the themes of family and childhood. The artwork may take any form/style but must be inspired by an artist you have studied on this course. The piece must include some representation (symbolic or literal) of yourself and at least three of the following:

Siblings, parents or grandparents

Family home

Childhood games/activities

Memorable childhood places

Childhood playmates

School

Birthdays or other family celebrations

This piece is 30% of your second year marks.

I stare at my name, written in spiky pencil letters top left: Kaylynn Ryan. I mouth the four syllables, kay-lin-rye-ann, that tell me who I am and wonder again if what I’m painting is fair, to them or me. I toss the paper down. Fourteen months and four hundred miles between us but I’m still not free of them. I glance around the studio. The others are cracking on; this is no big deal to them and they wouldn’t get why it is for me, which is why I haven’t bothered telling them.

Col and Rich are doing something with clay. Keith’s gone for a collage and Stu for some modern construction using bric-a-brac. Baz’s tapping a Warhol vein and Jeff’s being ironic with Hopper. Alex hasn’t even bothered showing up. Mr Simons wafts into the studio, mug in hand.

‘How are we all?’

There’s a muttered reply. I glance at him, at Alex’s empty place and back at Mr Simons.

‘Anyone seen Alex?’ he asks, looking at me.

‘He’s doing field research, for an installation,’ Col says.

‘In the Field Head,’ I correct, ‘for a pint.’

Mr Simons nods like he’ll do something about that later. He won’t. Not as long as Alex’s mummy and daddy keep coughing up generous donations to the art department. I shake my head, reminding myself to think tactical. It pisses me off that the system is so easily corrupted but their money buys us better paints, easels that don’t collapse, sable hair brushes. It can’t buy Alex any talent. Shame. Pity. Tragedy. I’m still smiling as Mr Simons starts his rounds, heading first to Barb, Sandy and Lisa’s knot of industry.

Sandy’s painting onto a tapestry canvas that she’ll embroider over later, her idea of empowerment she says, reclaiming the feminine arts. Yesterday Mr Simons praised her ‘modern feminist approach to liberating female expression’. Last night I overheard her telling the other two she’s worried her boyfriend’ll dump her because her boobs aren’t big enough. I considered piping up with the adage ‘anything more than a handful’s a waste’ but they don’t get stuff like that. Or people like me.

I pick up my fine brush and go back to the intricate tartan pattern adorning the ducks clustered around the pond in the canvas’s bottom left corner. Just because I’d rather not do this doesn’t mean I won’t.

Mr Simons clacks across the room on slippery brogues. I feel the heat from his body as he takes up position behind me, viewing my work.

Everything is outlined and bits of it painted. It’s going to be good, maybe even great, when it’s done. I’ve adopted Dali because surrealist symbolism is the only way to paint my childhood. My brushwork has the Catalan master’s accurate touch, the reality that battles hard against the weird in his work and, now, mine. The background is vague mountains that could be Catalonia or Scotland. The foreground’s rundown terraced street merges into a well-groomed city park. Half finished there’s enough for Mr Simons to see the whole, disapprove of the aesthetic but grudgingly admire the skill.

‘Very vivid. Talk me through this, Kaylynn.’

‘I thought art was ‘beyond explanation’,’ I remind him.

‘The external moderator will expect you to be able to discuss your work,’ he says. ‘This is your family home?’

He points to the row of cowering houses that falls off the right hand edge of the canvas. The red brick is soot-blackened, the windows are grey-grimed, the impression that of dereliction and imminent demolition. Only one house is a home, evidenced by an empty milk bottle on the step, the peeling-paint door ajar and three figures on the kerb in front of it.

‘Yes.’ One of them. The one that provokes the fewest questions about a childhood spent championing causes and fighting for freedoms. I should’ve let myself off, painted an easy lie, suburban and semi-detached. Or maybe I should’ve red-lined it and rendered resplendent the dented Transit van whose petrol-fumed interior gave me headaches; the caravan so cold icicles hung inside it, unfestive decorations; the fifteenth floor squat that wasn’t worth the climb or the castle commune that sheltered a dozen free-love couples, their placards and their children.

‘And these are your parents?’

Standing in front of the house are a man and woman, him in jeans, her in a floral smock. Where their faces should be there are protest posters, his of the Socialist Workers Party, hers of the Women’s Lib. movement. Both share the raised fist logo, hers inside the ♀ symbol and his on a red background.

‘Yes.’

‘Their faces…?’

‘Representative. Signifiers.’

‘They’re activists, are they?’ he asks. There’s no need for me to reply. He coughs. Continues. ‘And this?’

He waves his hand at the third figure, sandwiched between the mother and father. It’s constructed from slogans and symbols: a CND badge for a head; arms and legs made of words (free women’s bodies, capitalism is slavery, fur is murder, make love not war) and dressed in torn jeans and a T-shirt with the ying-yang Anti-apartheid movement logo on it. The parents have their arms stretched out as though holding the hands of the child that’s not a child. There aren’t any hands to hold; I’m not there. I’ve released myself back into captivity.

I loop my fingers through the chain around my neck, winding it up until I reach the locket, and stroke the shallow dent on the back with my thumb. ‘It’s symbolic.’

‘Of?’

‘Their child.’

Mr Simons scrats at his goatee and moves on, indicating the image’s central portion which shows the flesh-and-blood me, my fair hair cropped, my red duffle-coated back turned to the viewer. I’m three or four. Next to me is a boy not much older. Around us the flock of tartan ducks, waiting for my brush to fledge their check-and-line feathers, clap their wings. On the ground beside us is the stooping shadow of an old man I can’t paint any other way because I don’t remember him properly. But he was there, once.

‘Is this also symbolic?’

I won’t tell him it’s simpler than that: just a happy memory.

I trudge home to my digs through teatime twilight.

Around the corner a terrace of houses banks up like a cliff-face, four storey Georgian grandeur run down to twentieth century scruff. I stop at no. twenty-five and squint at my attic room. Grey light masks blistered paint, mould-coated

rendering and cracked glass. I climb the steps and enter the draughty hallway. Breath held to keep out the familiar stench of boiled cabbage and piss, I traipse upstairs. On the top landing I wrestle my door open, stumble in, dump my rucksack, hang my jacket and flick on the light.

Blue-white fluorescence stabs my eyeballs. Crumb-covered plates and mucky mugs sneer at me from the table. I stride over and grab three cups. As I lift them a misplaced patch of darkness on the table snags my eye. I stare. The dark patch becomes two oblongs, joined at right-angles. My heart crams up against the bottom of my throat. The mugs slip from my pincered grip. I cast off for explanations. My brain dumps everything, smearing images, fusing sounds; colours become blackness and noise silence.

I extend a finger. When I touch it, it will burst and vanish. My finger presses down. Cold hard metal presses back. There is no pop. The gun is real.

Someone flushes my toilet. I spin round to face the bathroom door. A man emerges. His eyes leap to me, drop to the gun, my finger stroking the stubby barrel. The glance forbids, cautions, tempts, suggests: don’t walk on the grass; no smoking; don’t press that red button. Better in my hand than his. I coil my fingers around the gun. It resists, dragging its weight as I lift it, metal fighting a magnetic draw. I pull it out and point it at him. He raises his arms, hands open, palms facing me, cautioning me like you would a running child.

‘Whoa there, go steady. That thing’s loaded.’

His words lilt with an accent: ‘dat’ and ‘ting’.

Scanning him from toe to top I note the scuffed boots, raggy jeans, scuffed leather jacket, two days’ stubble, blue eyes ringed with tiredness, dark unbrushed hair, tall and thin, scar on his cheek, about twenty.

‘Ah, come on, now,’ he coaxes.

I can’t speak. I’m not breathing. I fight to keep my hand steady, the gun from shaking. It’s heavy, solid. Sweat slicks my palm making the handle slippery. We’ve been like this for seconds, minutes: hours. I’ve forgotten how it started. I don’t know how I’m meant to end it.

‘Who are you? What do you want?’

‘Do you not remember me?’

I’ve seen those eyes before, somewhere, somewhen. Mute, I sift back through days, weeks, months, trying to locate him. He blinks twice.

‘It’s me, Aiden, Aiden O’Neill. Jesus, I thought you’d remember wee Aidie.’

I keep sifting; years fall through my fingers. Two kids run towards a pond. Ducks quack and flap.

‘How are ya, Caoilainn?’

He says ‘Kee-lun!’, not ‘Kay-lin’. The syllables buffet me.

‘That’s not how you say it.’

‘Sure, it is. A-o-i is ‘ee’ in Irish.’ His words have a teacher’s firmness. It fades. His eyes dart about. ‘You used to…’

‘I don’t... I can’t…’ I do. I can. Don’t want to. Am afraid to. A sing-songy voice chants in my ear: c-a-o i-l-a i-n-n, Caoilainn fair and Caoilainn slender; that’s my name, so sweet and tender. Whose voice? Whose rhyme?

‘I’ve something for you. I’m just after reaching into my pocket.’ He inches a hand inside his jacket. I tighten my grip on the gun, arm straining against the weight. He withdraws a square of card, pinched between finger and thumb.

I step forward, snatch the card and retreat, keeping the gun pointed at him. Flipping the card over, I see a black and white image of an old man and a young girl. Behind them is the columned entrance of a grand building. To their left squats a mound of rubble topped with an oversized stone head. Fluttering panic settles in my throat. The man wears a shabby suit and macintosh. The girl is wrapped in a dark duffle coat, booties and mittens. I know the coat is crimson. The girl is me. So the man holding my hand must be my time-shadowed grandfather.

When I look up Aiden’s closed in on me, has his hand on the gun. He tugs gently; I let go. He pulls out a chair and nudges me onto it. I don’t see him put the gun away, it’s just gone and he’s ruffling his hair. He takes out cigarettes, lighting one and giving it to me because either I smoke or I’m about to start.

‘I’ll put the kettle on.’ He goes to the sink.

Fixed on the photograph, I hear water gushing, a click as he lights the stove. The kettle whistles. He sets down two mugs, fetches the milk. I smell old sweat and wonder when he last showered and changed, slept in a bed: put down his gun.

Why the hell does he have a gun?

He sits opposite. We stare at each other. I study the scar. It’s three inches long and curved like a smile. There’s a fresh redness to it. Guided by my stare, he rubs a finger along it.

‘Sorry for giving you a scare. I’d no business leaving that thing on your table.’

‘Why’d you even have it?’

‘Just in case.’

‘Of what?’

He doesn’t reply.

‘You should be more careful.’

‘Aye, me ma’s always saying what a slapdash bugger I am but I never thought you’d go pointing it at me. I thought you’d remember me.’ A cough rasps in his throat. ‘You shouldn’t go aiming guns at people unless you’re meaning to shoot them.’

‘What makes you think I wasn’t?’

He riffles fingers through his hair again. I return to the photo, calculating my age to about four, making it a fourteen year old snap.

‘We used to feed the ducks.’

‘On the Green.’ He grins.

‘In Glasgow.’

His grin shrinks. ‘Sure, it was Dublin. That’s O’Connell Street.’ He taps the man in the picture. ‘Your…’

At the mention of Dublin a lost word appears.

‘Daideo.’

‘Aye, your granddaddy.’

My memories aren’t where I left them. ‘I don’t understand.’ I tap ash off my cigarette with shaking fingers. ‘We lived in Scotland, moved to England when I was nearly four.’

‘That’s what they’ve had you thinking?’ Aiden asks. He drops his gaze, gulps his tea. ‘Do you not remember Ireland at all?’

‘I remember the duck pond.’ I look at his eyes. ‘You.’ I take up the photograph. ‘Rainy days colouring-in. My name, the way you said it. The rest is hazy, a dream I know I’ve had but can’t recall. Jesus Christ, this isn’t happening.’ I sit back, close my eyes, reach down through the blackness and see a single point of light, fizzing like a dying firework. It runs off into darkness; there’s a loud bang, a white flash. Black turns orange and a small man falls from a great height. A voice rasps, ‘If things aren’t fair, you fight ’em.’ His words. Daideo.

Stroking the photograph, I feel skin, warm, rough and crinkly. ‘He died after we moved.’

‘He didn’t, Caoilainn.’

‘Shit.’ I lean forward, sick and dizzy. ‘I don’t understand.’

Aiden takes my hand. ‘I’m sorry for bringing this to you but we had to. He’s not well, not well at all.’

‘So they fell out? And now he’s dying he wants to make it up?’

Aiden shakes his head. ‘He doesn’t know I’m here. He won’t have doctors so we don’t know how bad he is, but it’s plain he’s ill. We’ve been worrying about what to do.’ A frown creases his forehead.

‘We?’

‘Me and my ma and da, especially Da. He’s been frantic about it, so he has. Feared of your granddaddy being on his own when he...’ Aiden withdraws his hand and drags on his cigarette.

Coldness spreads through me. I swirl my mug. A picture develops in the darkroom of my memory, of a few more lads, dressed like Aiden but with balaclavas. I’m not sure it’s real. Then one of them moves a hand to his head, trying to ruffle hair covered by a woolly mask. My mouth fills with the sweet sharp tang of a strawberry lollipop.

‘Your dad…’

‘You remember him?’

‘He always had sweets for us.’

‘Aye, and you got the strawberry ones. Dead jealous of that, so I was.’

I pick over charred memories, shuffling and sorting until there’s something readable.

‘So you

’ve taken up the family business.’

He fiddles with his cigarettes.

‘The IRA,’ I press.

‘Why would you be saying a thing like that?’

‘You’re Irish. You have a gun. It’s not the Times crossword.’ I jab at the photograph. ‘That’s why they moved, told me he died, isn’t it?’

I push the picture away and stand up, knocking over my chair. Aiden grabs my wrist.

‘He’s a hero, your granddaddy, and he should have his family around him now he’s…’ Aiden’s fingers squeeze.

I pull free. ‘How did you even find me?’

‘Your granddaddy gets letters, four a year, telling him what you’re up to. I swiped a look at the most recent, got your address.’

‘Letters? From my parents?’

Aiden shrugs.

‘This makes no bloody sense. Why would they write to him about me but have me think he’s dead?’ I demand.

‘Dunno.’ He scans the room as though he might find an answer among my clutter. ‘Look, I’m just after you coming home with me.’

‘No.’

‘Jesus, he’s your kin.’

‘So? I haven’t seen him since…’ I glance at the photo. ‘You’re mad to think I’m dropping everything and rushing off with you. Get Mum to go. He’s her dad, she can deal with it.’

‘Ah, shite.’ Aiden backs away from me, worries at his hair.

Fear coats my tongue, the bitter taste of orange pith. ‘What?’

He rights my up-tipped chair, drops a hand onto my shoulder and eases me down. ‘You don’t want to hear this from me.’

And now I have to. I stalemate him. ‘I’m doing nothing until you tell me what’s going on.’

‘Just come.’

‘Tell me first.’

‘Then you’ll come?’

Like hell. Maybe. Depends. I say nothing; the silence forces words from him.

‘Da wasn’t sure what you’d know, how much you’d remember…’ He reaches into his pocket again, pulling out a yellowed piece of paper. He sets it on the table but keeps a hand over it.

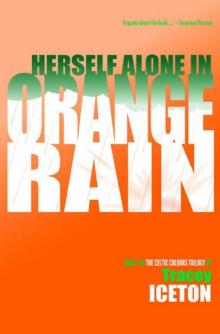

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain