- Home

- Tracey Iceton

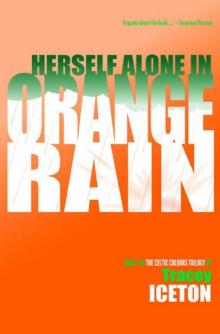

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Page 14

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Page 14

The O’Neills terrace house fills up with friends, family and festivities. On Christmas Eve I’m crammed into the kitchen with Nora and Cathy, peeling spuds, chopping carrots and mixing sludgy stuffing. In the front room Frank drinks with Patsy and two other cronies from the Felon’s. Danny and Callum are upstairs, keeping out of the way.

Nora takes more beer into the front. Cathy tips the contents of her teacup down the drain.

‘Sure, I’ve been gagging for herself to slip out,’ she mutters, pulling a hip flask from her pinny pocket and refilling her cup. ‘Don’t I miss your ma on days like this? She would’ve played merry hell if Nora so much as tutted over us having a tipple. Would you take a wee drop? It’s only firewater but it does the trick.’

I grin at her. ‘Thanks.’

She brims my cup then raises her own. ‘To Christmas with family and please God may I survive it.’ She tips the rest of the hip flask’s contents into the stuffing with a chuckle.

Danny, Callum and I drape the spindly tree with the last strand of silvery tinsel. I lift Callum so he can sit the star on top, my arms trembling with the strain as he adjusts and readjusts until the star is perfect. I’m relieved to put him down. We step back. Fairy lights glitter and baubles gleam. Danny throws his arm around Callum’s shoulder and they stand admiring our festive installation. Callum wriggles warm fingers in amongst mine. I fight the urge to retreat; I need to be better at this.

Nora comes into the sitting room. The pinny has been replaced by her Sunday best.

‘Yous two, away and get dressed.’ She shoos them out. Coming to me, she holds up a square of black lace netting, like a veil from a funeral bonnet. ‘You can borrow this.’

I take it, rubbing the coarse mesh between my fingers. ‘What for?’

‘To cover your head, unless you’ve a hat?’

My hand strays to my hair. ‘Why do I need to cover my head?’

Nora tuts. ‘I don’t know what you’ve been used to but here we’re modest in church.’

The clock chimes 11 P.M.; I click on and return the headscarf. ‘Thanks but I’m not going to church.’

The fabric wilts in her stunned hand. ‘You can’t mean to miss midnight mass? That’s awful, so it is.’

‘Only if I’m Catholic.’

‘Oh.’ A single syllable, not even a word, but it sounds out her dismay, disappointment, disapproval.

‘Daideo didn’t have time for it and my… the Ryans didn’t believe in slavishly following dogmatic religious regimes. They were more into the comparative study of spirituality.’

She stands over me, arms folded, eyes narrowed. ‘I see.’

I lock my eyes into hers. Nora wads the headscarf in her fist, crosses herself with two sharp swipes of her hand, spins on her heel and strides out. A moment later I hear muttering in the hall; she’s telling Frank and Cathy about the wee heathen on the couch. She shouts for Danny and Callum to hurry up. They stampede down the stairs. There’s scuffling; shoes donned, coats buttoned. Franks calls:

‘We’re away, Caoilainn, love. See you in a bit.’

‘Fine.’

The front door slams, shaking the Christmas tree. Alone for the first time since I arrived, I go to the bedroom I’m sharing with Cathy and retrieve my gifts, putting them under the twinkling tree, all but the reindeer-wrapped box. That I open myself, tearing off the Rudolph paper. Cleaned and docile, the gun nestles on tissue paper, the almost full magazine beside it. I load it, replace it in the box and slide it under my bed, wondering who to give it to.

On Christmas morning paper is ripped, kisses and thank-yous exchanged. The kettle is on constant boil and a whole loaf is toasted and buttered. Then it’s church again. Nora leaves me orders for setting the lunch away, my penance for shunning her God; I baste chicken and boil potatoes while they’re on their knees. At two o’clock we eat, drink, pull crackers, don paper hats and tell stupid jokes: why does Santa have a big garden? Because he likes to Ho Ho Ho! Nora carries through the pudding but Frank can’t get the brandy to light.

‘There’s not enough oomph in this cheap piss,’ he moans.

‘I’ve heard vodka works better,’ I say.

He snorts, ‘It’s bleeding petrol we’re needing.’

‘Frank!’ Nora snaps.

‘Aye, well, wouldn’t be doing much for the taste of it,’ he admits, passing round bowls, each containing a mountain of pud, snow-capped with thick rum sauce.

After lunch, when, in another life, I’d have been dragged out to picket capitalist commercialism or hand soup to the homeless, Danny is propelled onto the hearth rug. He sings ‘The Wearing of the Green’ with a choirboy’s voice.

As he finishes an assortment of neighbourhood friends cram into the front room, perching on chair arms or leaning against the sideboard, mantelpiece, windowsill. Among them is Liam. His black hair is shorter. He’s wearing a shirt and tie. Cleaned up and clean-shaven he’s a good looking lad. He waves to me and smiles. A flicker on the edge of my vision makes me turn. Nora is staring at me. Unjustified heat flushes my face. I excuse myself, go into the kitchen and start scraping grease from a roasting pan with a wooden spoon.

‘Caoilainn, how are ya?’

Liam’s greeting startles me.

‘Fine, yourself?’

‘Aye.’ I hear the door click shut. ‘Heard about what happened. Good on ya.’

I face him now. He comes closer.

‘What d’ya mean?

He smiles. ‘You didn’t panic, got yourself away. Spot on.’

‘I shot the wrong man.’

‘You did what you had to.’ He lays his hands on my shoulders. ‘It’s the way things go sometimes.’ He steps back. ‘If you’re about later there’s someone wanting to meet you.’

‘Who?’

‘My OC.’

I think of the gun. ‘Alright. I’ve something for him.’

Liam raises his eyebrows. ‘What’s that?’

‘Something I’ve no business having.’

The door swings opens. Cathy sashays into the kitchen, sees us and pulls up.

‘What’s this, a cosy wee tête-à-tête?’

‘We’re catching up,’ I say.

‘See you later,’ Liam mumbles, squirming past her.

Cathy closes the door. ‘Know him, do you?’

‘We went through basic training together.’

She chews her lip. ‘Watch yourself; there’ll be talk if you’re sneaking off with lads.’

I clatter the spoon into the sink. ‘Talk?’

‘You’re an O’Neill now, as good as. You need to mind that. People here have fixed ideas. I know the cost of going against that so take my advice: remember whose house you’re in.’

‘Did Frank send you to spy on me?’

‘Frank?’ Cathy snorts his name. ‘It’s not him you’ve to bother about. It’s the mammy. It’s always the mammy with Catholic boys.’

‘Especially when the girlfriend’s not Virgin Mary white?’ I ask.

‘Aye, you’re catching on,’ Cathy replies. ‘Your ma’d be proud.’

The neighbours head on somewhere else. We play charades; Danny sings more rebel songs. Frank falls to snoring in front of the box while the boys start a snakes and ladders game. The washing up done, Nora, Cathy and I make tea. I butter bread, Cathy slices cucumber while Nora validates tinned salmon with white pepper and malt vinegar. Our jobs, assigned by Nora, reflect our family ranking.

Liam taps on the window. Nora sets her fork down, wipes her hands, pats her stiff perm, strolls to the door and opens it. Cathy nudges me and, with a flick of her eyes, repeats her warning. I scrape a buttery curl from the yellow brick and spread it unevenly on a white slice, tearing the bread.

‘What can I do for you, Liam?’ Nora asks.

‘Hello, Mrs O’Neill. I’m just after five minutes with Caoilainn.’

Nora scans him. The shirt and tie have been replaced with a sweater and a donkey jacket. He shuffles under her scrutiny.

‘Importa

nt, is it?’ she sniffs.

‘Aye, it’s,’ he lowers his voice, ‘Army business.’

‘Today?’

Liam glances at me. Cathy hisses in my ear.

I put the knife aside. ‘I’ll get my coat.’

Upstairs I retrieve the gun, hiding it under my sweatshirt, fastening my coat over it. Danny waylays me in the hall.

‘Where’re ya going?’

‘Never you mind.’

‘Can I come?’

‘Aren’t you playing with Callum?’

‘I’m bored.’

‘I won’t be long. When I get back you can teach me those songs.’

He pulls a face. ‘I know where you’re going.’

‘Then you know why you can’t come,’ I reply, entering the kitchen to hear Cathy asking Liam if he has a girlfriend.

‘Sure, I’ve no time for that,’ he says, his face pinking.

‘Let’s go.’ I cut through them, shove Liam outside, cross the yard and head into the alley.

‘What’s up with Aiden’s ma?’ he asks as he leads me along the lane.

‘She thinks I’m after sleeping with you.’

‘Eh?’ He halts, turns a stunned expression on me.

‘Seems we can either be good Catholic girls or hoors. As I’m not the first I must be the other.’ I walk on, stamping down my anger. After a few paces Liam recovers and catches me up.

We go into a backyard a dozen houses down the alleyway; Liam knocks on the door. It’s opened by a short, wiry man in his thirties, his receding hair cropped close. He’s wearing a navy jumper with a snowflake pattern.

‘Sean.’

‘Liam.’ He reaches out and slaps Liam’s shoulder. ‘Away, yous are letting in a draught.’

We go into the front. He takes a bottle of Bushmills and two tumblers from the sideboard.

‘Drink?’

‘Cheers,’ Liam says.

We sit and Sean pours, topping up his own glass first.

‘How’re things in Dublin?’

‘Quiet.’

He nods.

I want this over with. I set the gun on the coffee table.

‘I realise I should’ve handed this in straight away but…’ I trail off, rejecting lame excuses that won’t save me from the bollocking I’m overdue.

He barely glances at it. ‘No harm. Beginner’s mistake.’

‘Not my only one.’

He leans forward, raps on the table.

‘Says who, that gobshite Kelly? Don’t listen to that bollocks. He’s up to his armpits in the kinda shit that gets us a bad name. If I’d any say he’s be out on his elbow for bringing the Movement into disrepute, the racketeering sod. He’s only for himself, so he is. Wants to play the big man. We’re not all like him.’

‘So you don’t think I should be at home making bread and having babies?’

‘Not if you’d rather be shooting Brits, which I’m guessing from what happened with that operation, you would. Took some nerve, that did.’

‘It was a fuck up.’

He raises his eyebrows.

‘And I’m not apologising for my language.’

He smirks. ‘I’m not after you to. Swear like a sailor, if you want. I couldn’t give a shite about your vocabulary.’ The smirk vanishes. ‘It’s your actions and your attitude I’m keen on.’ He lights a cigarette, pushes his pack towards me. ‘So have a word with yourself, calm down and listen.’

I take the cigarette and the advice.

‘What happened was regrettable but sometimes missions misfire; it’s your fault, some other bugger’s fault, God, fate, blame who you want.’ He shrugs. ‘What matters is how you deal with it. You were right doing what you did.’

‘You’re making it sound like I knew what I was doing when it was only instinct.’

‘Then your instincts are dead on, and so are you from what I’ve heard.’

‘From who?’

‘Frank. If he’s up for you, that’s better than a blessing from the Pope.’ Seeing my confusion Sean adds, ‘Did you not know he was on the Army Council when we first split from the Sticks? Big man, so he was. Still is.’

‘I’m here on his word, then.’

Sean bangs his glass down. ‘Frank gives no favours and neither do I. The lives of my volunteers are too important for bullshit like that.’ He leans back, swilling his whiskey. ‘We’ve had a lad lifted by the Brits. I’m needing a replacement: you, if you’re keen.’

‘I am.’

‘Grand. I’ll need you here as of now, mind.’

‘Fine.’

He offers me his hand. ‘Frank said you’re Pat Finnighan’s…’

A noise outside, someone hand-clapping a staccato rhythm, interrupts. Sean leaps to the window and tears aside the curtain.

‘Jesus. Liam, go for Rory. Get the Armalites. There’s shooting up the road.’

We’re both on our feet.

‘Where?’ Liam asks.

Sean faces me. ‘The O’Neills’.’

I grab the gun and dart for the door.

A dark car and a pale van are askew in the street outside Frank and Nora’s, doors open, headlights blazing. Gunfire chatters through the air. I run towards it; someone gets out of the van, the dazzling headlights illuminating a tall, stocky, masked figure, arm raised. There’s a bang and a flash as he fires at me. I stop and aim, gripping the gun in both hands, drawing a breath and squeezing the trigger. The kickback jolts me. The man stumbles, scrambles for cover inside the van. I fire again. Four more masked men run into the street, lit up by the glittering fairy lights Danny, Callum and I wound around the tree in the bay window yesterday.

Engines roar; the attackers dart to their getaways. Behind me two Armalites spit bullets at the car and van, blowing out a headlight, shattering a windscreen, denting a door. The car speeds off. I start running again. The van swings into a miscalculated three-point turn, ramping over the kerb, ramming a lamppost, bumping down, charging across the road and smacking a parked car. I fire, once at the passenger window, twice into the side of the van. It stalls. I leap forward, am yanked back by Liam. He aims at the van. Another lad, Rory, I guess, falls in beside him and, synchronised, they fire as the van stutters to life, limping beyond range.

I break away from them, running to the smashed front door. The Christmas wreath is pulped on the welcome mat, the air thick with acrid smoke. I plough through it, up the passage.

Cathy is crumpled in the lounge doorway, her head lolling backwards, her legs folded under her. The front of her white, lace-neck jumper is a red, ragged mess.

‘Jesus,’ Liam says.

I smell the cordite from his rifle; he’s right behind me. I step forward. He catches my arm.

‘Don’t.’

I jerk free.

Frank is sprawled on the sofa, his face ashen and contorted by pain, his knees shot away. White fragments of bone gleam and blood pumps down his legs, soaking his trousers, slippers, the carpet. Nora crouches beside him, fumbling with a towel, keening a stream of urgent Latin. Danny stands on the hearth rug, from where, hours earlier, he’d sung to us. His hands are clenched, his eyes fixed on his daddy. The snakes and ladders board is at his feet, Callum sat beside it. His new Ireland jersey is blood-spattered, chunks of pinky flesh are in his hair, on his face. I go to them, putting the gun in my belt, hauling Callum up, snatching at Danny.

‘Get off,’ he shouts, shoving me away.

I slap his cheek. His face fractures, tears bubbling over. Pretending not to see I lift Callum, balancing him on my hip, and turn so he can’t see his murdered mammy in the doorway. Holding him with one hand, I grab Danny’s shirt and tow him along. Liam is waiting in the hall, his weapon propped against the stairs. He swings Danny out of the room; I step over Cathy, Callum clinging to me. Sean and Rory are here now, Rory guarding the entrance, facing out. I take in the back of his ginger head, the grey t-shirt, faded jeans, red and green striped socks; he didn’t wait to put boots on. Shouts from fretful neighb

ours, already mourning another death, flutter in to us.

Sean takes Callum from me. My sweatshirt feels wet. I look down, see the damp patch, transferred from Callum’s crotch. Sean pulls Danny and Callum together, pointing them down the passage.

‘Get yourselves into the kitchen,’ he orders.

Danny glances at me.

‘Now,’ Sean barks and Danny leads Callum away.

‘We need to go,’ Sean says.

‘I can’t leave them like this.’ I gesture to Cathy: Cathy’s corpse.

‘It’s not up for discussion,’ he says. ‘Peelers’ll be coming. If you want to be useful it’s better they don’t know you exist so get your stuff now.’

Grasping at torn parts of myself, I take the stairs two at a time, bundle my things into my holdall and race down. Rory moves aside; Sean, Liam and I step out, Liam carrying his gun down by his leg. Rory follows. The crowd closes round us, led by Patsy.

He calls to Sean, ‘Ambulance is coming. I’ll take care of everything.’

Sean nods. The crowd parts and we head up the street, through a door opened and waiting, into a house, out the back, over the alley, into another house, through that to a waiting car and off across the city, Rory driving, Sean beside him, Liam and me in the back.

‘You alright?’ Liam asks.

‘Have you a cigarette?’

He gives me one, lit, and I gulp at it.

‘Fucking bastards,’ Sean says, ‘on Christmas day.’

‘Who were they?’ I ask, cigarette shaking in my fingers, gun digging me in the back, the stench of smoke and piss churning my stomach.

‘UFF, hit squad for the UDA who’re just off-duty UDR pricks, service weapons handed out by the Brits and they don’t give a fuck what the fuckers do with ’em as long as they’re killing Catholics,’ Sean explodes. ‘There’ll be a payday on this.’ His words are black underlined. They rule us off into temporary silence.

Sean twists round. ‘You’re a canny shot.’

‘I missed.’

‘Looked to me like you got him in the shoulder.’

‘I was aiming for his head.’

‘At fifty yards with half the streetlights out? You always this hard on yourself?’ he asks.

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain