- Home

- Tracey Iceton

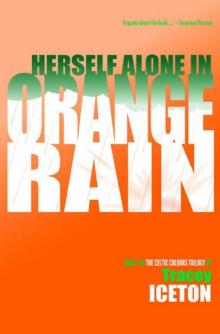

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Page 7

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Page 7

His drinking companions slope off. Frank pulls up a stool for me. ‘How’s the ould fella? Better for having you around?’

I sip the whiskey. It burns my throat. ‘I suppose.’

‘Grand.’ He hurries on. ‘Have yous somewhere to stay tonight? We’d have you home but for the bloody Brits.’

‘It’s sorted,’ Aiden says. ‘Have you heard from Connor?’

‘He got a comm out last week. He’s coping. Your ma’s upset though.’ Frank lowers his voice. ‘There’s talk of a second strike. They got nothing from the last. Connor’s put in for it.’

Aiden downs his whiskey and taps the glass on the bar; the barman takes it for refilling. I can’t ask Frank about my parents now: present trumps past. Not wanting to intrude on their family crisis I look around, spot the toilets and get up. Crossing the room I pass a framed black and white photograph of five smiling lads: friends, larking about. Hung beneath is a wooden plaque engraved with their names and ages; all dead before they reached twenty-one. Next to it is a poster promoting the New Year’s Eve party. Life’s relentlessness winds me.

‘You alright there, love?’ One of Frank’s cronies is at my elbow. He smiles.

‘Yes, thanks. Just looking around.’ I nod to the picture.

The smile snaps into a scowl. ‘For what?’

‘Nothing, I…’

Aiden appears. ‘She’s with me, Peadar. We’re going.’ He grabs my arm.

Peadar’s scowl fades. ‘Sure, that’s fine.’ He switches the smile back on. ‘You were gave me a scare then,’ he chuckles. ‘Thought we’d let in a spy.’

‘What?’

‘Your accent, love. You sound like a bloody Brit.’ He’s grinning when he says it. The words cut through me.

Aiden mutters, ‘Christ sake,’ and tows me towards the fire exit. I twist round. Peadar is staring and, behind him, Frank watches us from the bar, his face pinched. Aiden lets go of my arm to smack the door open with both hands. He charges through it. I stumble after him, into an unlit side road, the words ‘bloody Brit’ chasing me.

Squinting against the darkness, I find the car. Aiden’s in the driving seat. I climb in.

‘Cheeky sod, did you hear that?’

‘Shut up.’

‘He said…’

‘Wise up. My brother’s gonna starve himself to death and you’re whingeing about your accent,’ Aiden snaps. ‘You do sound like a fucking Brit. So just shut the hell up.’

We sit there for a minute, two, three. Furious words rage through my head, flood my mouth. I face Aiden, am about to deluge him with curses when I notice his shoulders shaking. I face front again. On the edge of my vision I see him put a hand up, rub his eyes. He sniffs once. Then starts the car and drives methodically at 30mph up the Falls, across the city, passing the floodlit City Hall, and over the river where he takes a left, parking by a house, the windows boarded and ‘Taigs Out’ daubed across the door in blood-red paint.

‘This is us.’ He plucks a torch from the glove box and gets out.

A shudder runs across my back. I wait a second before following, giving us both time to pull ourselves together.

The house reeks of damp. There’s no power; Aiden guides us with the torch. In the living room an old sofa is pushed against one wall, the cushions ripped, stuffing oozing out. A sideboard lies up-tipped under the window. I pull my coat tighter.

‘Have you seen enough?’

I nod.

‘We’ll drive back tomorrow,’ he says, reaching for my hand. ‘Sorry for saying that before, about you sounding… ya know.’

‘It’s true, though. It’s why they didn’t have me spread out on the tarmac at the border. It’s what I am.’

‘You were always Irish, you just didn’t know it,’ Aiden corrects.

‘And knowing’s enough, is it?’

He squeezes my hand. ‘There’s a chippy on the corner. You hungry?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I’ll be five minutes.’ He gives me the torch and leaves before I can say I’m sorry too.

While he’s gone I roam the house, sweeping each room with the narrow white beam. Floorboards are peeled back like banana skins. In the kitchen there’s a broken table and the splintered legs of several chairs. Cupboard doors hang on wrenched hinges. The bathroom sink has been pulled off and dumped inside the bath. Slimy water lurks in the toilet bowl. One bedroom has a stained mattress on the floor, another a smashed wardrobe. A teddy bear lies facedown on the bare floor. I pick it up, stroke an ear, and carry him with me.

Clutching ted I retreat downstairs, and sag into the sofa, sinking down through Kapok and memories. I flick the torch off and stare into blackness, squeezing ted, wondering about the child forced to leave him behind in the chaos of fleeing from neighbours wielding clubs, petrol bombs, maybe even guns?

I was seven, eight? We were squatting, camping I’d been told, in a boarded-up house on a ready-for-the-bulldozers estate…

‘Why do we have to stay here, Mummy?’

‘We’re protecting these people’s homes.’

‘It smells. I don’t want to stay here.’

‘If we don’t stay, love, who’ll stop these homes being destroyed?’

‘Can’t the police do that, Mummy?’

‘What’ve I said about not trusting the police, love? You mustn’t trust anyone with that much power; they always abuse it.’

‘What’s ‘abuse’?’

‘They do what’s best for themselves and don’t care if they hurt others. The police, the armed forces, big corporations, politicians; they’re all too powerful for our good so it’s up to us to keep ourselves and others safe from them, from all powerful bullies and bad guys. That’s why we’re here. It’s important.’…

It was always bloody important.

But never as important as this.

The police came to evict us. There was a lot of noise; shouting, banging. I was led outside. A policewoman lifted me into a van. I wouldn’t tell her my name.

The front door clacks, jarring me out of the remembered nightmare, into the real one. I cram ted into the sofa’s guts.

Aiden has brought cod and chips twice. The greasy smell hangs like fog in the cold air. We eat with our fingers. I bolt my food; Aiden rakes through his, eating hardly any. We smoke a while then he fetches a rug from the car and we huddle under it on the sofa, in our jackets. My feet are wet; their icy numbness nags me. I lie listening to Aiden’s rapid breathing. My mind flicks to the man being beaten at the checkpoint. I reach into the stuffing, slip ted from his hiding place and cuddle him to my chest. How did things get so bad in the north? How did we let it get this way? I don’t even know who ‘we’ is: British or Irish? I don’t know which side I’m on. In Belfast you have to take a side. But you don’t pick it; fate does that for you.

I wanted to understand the past but now I don’t recognise the present.

Voices shout. Glass breaks. Aiden sits up.

‘What’s going on?’ I ask.

He goes to the window. ‘Loyalist attack. Stay here.’ He strides to the door.

‘What’re you doing?’

He’s gone before I finish asking.

In the street people are running, men, boys, carrying bricks or bottles. Women watch from their doorsteps. Aiden steps out, waylaying one of the older men. They talk. The man points up the road; Aiden takes off. I run after him, against common sense and the growing mob’s current, stumbling as I struggle to keep Aiden in sight. He dashes into a house. I stop at the gate, see him through the open front door, standing in the hall, tucking a gun into the waistband of his jeans. A woman in dressing gown and slippers is with him. She sees me.

‘Who the fuck’re you?’ she bawls.

Aiden turns. ‘I told you to stay put. It’s alright, Mary, she’s with me.’ He comes over, grabs my arm. ‘Go back to the house.’

‘No.’

‘Fuck sake.’ He sprints into the street.

‘Leave it to the men, love,

they know what they’re doing,’ the woman says.

Do they? I want to laugh.

Aiden has vanished. I walk into the running crowd; people rush up behind me, charge into me and spin off, deflected. A few hundred yards down the road is a junction where the crowd crushes itself.

Yellow flashes light the scene. ‘Fenian bastards!’ ‘Taigs!’ ‘Orange scum!’ ‘Loyalist bollocks!’ Missiles are hurled. Others land around me with cracks and thumps. People retreat and reload, snatching up second-hand rocks, lobbing them back. Next to me a boy touches a match to a rag dangling from the neck of a milk bottle sloshing with murky fluid. The rag ignites. He chucks the bottle and I trace its trajectory, watching it shatter against the opposite kerb, spilling fire.

Waves of people sweep back and forth in the fighting’s swell. Something whacks me on the chest and I fall. Feet pound around me, over me. I curl into myself. Boots jab my back, land on my shoulder and lift off again as the runner vaults me. I get onto my knees and up, am shoved about. I wobble, clutching for something to hold onto, push off from. The darkness is lit by flaming puddles; I can’t tell friend from foe. Fear overwhelms me. I swing round, searching for Aiden, an exit: a weapon.

A brick crashes at my feet, chips off it spattering my legs. It happens in slow motion; I watch each shard fly free. Thoughts crystallise, step-by-step instructions. I pick it up, weigh it in my palm, arc my arm and throw. The weight leaves my hand and soars.

I try to follow its flight but lose it among others sailing through the air. I elbow to the edge of the mob, watching hunks of masonry curve up, over and smack down across the way. Some shatter, others bed in, scarring the road. A man is hit, his forehead split. He takes one pace and drops. The crowd swallows him. I’m suddenly afraid of myself. I’ve never fought like this before. I’ve never had to.

Bullets are spat into the air. There’s a second’s freeze frame then chaos restarts. A helicopter chatters across the sky, its spotlight piercing the crowd. Sirens scream. Around me the swarm swoops and dives, splitting and reforming. I’m pushed and pulled, dragged with it: part of it. I fight towards the ragged edge and glance back as now familiar grey Land Rovers plough into the churning surge of people.

The Land Rovers spew up policemen in riot gear.

Flames slice the blackness. The air ripples with the shattering of glass and clanging of brick on metal.

I’m grabbed, yanked backwards. It’s Aiden, cheek bruised and nose bloody.

‘We need to go,’ he yells.

He drags me into a running retreat, back to the violated house. We tumble inside, him shoving me, me tripping. He whacks the door shut and leaps over me. There’s the scudding screech of wood dragged across wood. He emerges towing the sideboard.

‘Gis a hand, will ya?’

I scramble up, take the other end and we wrestle it into place, barricading the front.

‘Don’t reckon they’ll check but in case,’ he mutters.

I lean against the wall, panting, shaking. In the darkness I lose Aiden.

The torch flashes on; its white beam inspects me.

‘Wise up; you can’t go jumping off like that. It was really stupid. You could’ve been hurt.’

Bruises throb across my back and chest. ‘So could you.’

‘I’m trained for this. You’re not.’

‘You reckon I’ve never been caught up in a riot before? What do you think the ’72 miners’ strikes were, a teddy bear’s picnic?’

‘You were a only a wee ’un then. And yous weren’t facing peelers with guns. Don’t kid on you know what you’re doing here. You don’t.’

‘And you do?’

‘Aye, this is what I grew up doing. Knowing. I’ve been at this since I was ten. So stop believing you can pick it up in an afternoon. You’ll get us both lifted. Or killed.’

His words slap sense into me. I push the torch away, getting the beam off my shame-scorched cheeks. My face cools. His breathing slows, quietens.

‘You OK?’ He puts a hand on my shoulder.

My tongue is dried up, my thoughts a wordless mess. He strokes the torchlight back over me.

‘You’re bleeding.’ He points to my face.

My cheek feels sticky. My fingers come away stained.

‘So are you.’

He wipes his nose with the palm of his hand, studies the inky smear.

‘I don’t want you getting hurt.’

‘What about you?’

‘That’s my choice.’ He laughs, rubs his hand on his jeans. ‘Some sodding choice. You know what they tell you when you join? That you’re heading one of two places: jail or the cemetery. But you join anyway ’cos this way you can defend your family, try to make things fairer, better. That’s what this war is, Caoilainn, fighting to make things better than they used to be which is nothing but year after bloody year, decades, centuries, like tonight and worse. How’s that for an education?’

It’s a start.

Belfast Man Dies Following

Newtownards Riots

Police Appeal for Witnesses

Six days after street disturbances in East Belfast, police have confirmed the death of William Stephenson, 50, of Newtownards Road.

Mr Stephenson, a Protestant, was injured on Boxing Day night when fighting broke out between locals from the Catholic enclave of Short Strand and Protestant residents in the area. Mr Stephenson was struck on the head by a missile and taken to Belfast City Hospital where he remained in critical condition until his death earlier today.

Police are appealing for information about the attack, which occurred as Mr Stephenson stood outside his house.

Mr Stephenson is not known to have any connections with paramilitary groupings.

Dublin—1st March, 1981

Second Maze Hunger Strike Starts

Republican Prisoner Bobby Sands

Refuses Food

Less than four months after the ending of a hunger strike by Republicans in the Maze Prison a second strike has begun today. The strike, announced by Sinn Fein, is in response to the failure of British officials to concede to demands made by IRA prisoners seeking political status.

A prison spokesman confirmed that Bobby Sands, 27, OC of the Republicans in the H-Blocks, has this morning refused food. It is believed this strike will be staged, with men joining at predetermined intervals.

In a statement issued by the Republican Press Centre, Belfast, Sands said, ‘Once again under the duress of the British barbarity and in the ugly face of further British intransigence, we are forced to embark upon a hunger strike. If the British Government cling to the forlorn hope that they can break the men of the H-Blocks they should look at their failures during the last four and half years of our protests. In one way or another, victory will be ours because we have the will to win.’

Downing Street has yet to comment on this second strike.

I give up on the past, focus on muddling through the present.

Daideo gives up on the future. He stops eating.

Every morning before college I cook a fry-up. He slowly chews one mouthful. I potter about the kitchen. He’s forced to swallow and start on a second forkful. I tie back my hair, lace up my trainers, pack my sketchpad. He carves off another bite. I collect the post, give Daideo the bills. He sets his fork down.

‘You’ll be late.’

‘I’ve plenty of time.’

He puts the third bite into his mouth. I butter bread, slice cheese, make sandwiches. One I thrust into my bag, the other I leave on a plate in the fridge.

‘See you tonight.’

‘Aye, off you go.’ He pats my arm with a skeletal hand.

When I get home the plate is on the table, empty; the sandwiches are in the bin. The crusts are curled, the cheese sweaty. If I’m lucky there are a couple of bites missing. I cook tea, eat, watch him cutting his food into ever smaller pieces, not eating. Gravy dregs solidify on my plate. Food petrifies on his. The bin fills up with a collage of rotting meals.

&nb

sp; He wants to die like this, cheating the cancer.

One night, as we stare at the telly, he says this is mine when he’s gone.

‘I’ve made a will, so I have, and been careful with my money. The house is paid off and there’s enough to keep you going a fair while. You can finish your studies, set yourself up with a studio, whatever you want.’

‘Don’t be daft,’ I reply, changing the channel before the news blurts hunger strike updates.

‘You’ve a talent; make better use of it than I did mine,’ he instructs. ‘Some day your work’ll be in one of those galleries on Temple Bar, maybe even the National, eh?’

‘And you’ll be at the opening with me.’

Another night he produces a brown envelope. He’s a plot bought and paid for in Milltown, an old Republican’s last home. I think of the graves that aren’t there: Cathal and Fiona. I couldn’t find them in Glasnevin either. But I still can’t bring myself to ask him about them and, apart from Frank, who I’m wary of bothering with this now he has a son readying for the hunger strike, there’s no one else I can ask. I shelve my questions.

‘Put what you want on my headstone,’ Daideo adds, ‘as long as it’s not religious. The priest’ll say his bit, those buggers get you in the end, but I’ll not spend eternity beneath their blasted blarney. Sure, He’ll not have the last word on me.’

‘You’ve years yet.’

‘I have not.’ He presses the envelope into my hands. ‘It’s arranged so see you mark my wishes: no prayers and no tears.’

Other times he tells me to go out, enjoy myself. My lack of friends makes him uneasy; his meant so much to him. He says it as I hand him supper: cocoa and barmbrack. He sips the chocolaty liquid and tucks crumbs of the fruit loaf into his mouth, never enough to finish the whole slice.

I swat away his words. I’ve never been anywhere long enough to make friends; I’m fine without. He flinches. I try to sooth. Anyway, I’d rather be home with him, recovering the time we’ve lost, time he robbed me of, time he’s stealing again. I get him tale-telling; a legend, a myth. Once I luck out, Daideo forgetting himself, his pain, and dipping into the family annals. He reveals how my ma and da met at a local dance, an ordinary story that didn’t deserve such a tragic ending. I lose myself in his memories; they paint over our cracked pasts, paste the present together.

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain