- Home

- Tracey Iceton

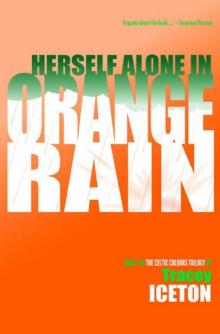

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Page 4

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Page 4

Silence smoothers us. I want to be sucked into a blinding, screaming vortex. I don’t, can’t, move.

Daideo hands Aiden the emptied cup and twists stiffly to the window. Outside darkness soaks the quiet street. ‘It’s late. You can stay tonight, then back to that college of yours tomorrow.’ He nods to Aiden. ‘Make up the spare bed, lad.’

In a voice half a toner higher than usual Aiden asks, ‘Shall I see about grub too?’

‘Can do,’ Daideo says.

Aiden ducks out.

A minute passes, and a second. Daideo doesn’t flinch. Sickening shame drains into my stomach. I stand and stagger from the room, following the clang of pans to the kitchen.

Aiden is at the sink.

I kick the door shut, press against it, panic piling on panic.

Aiden comes over, squeezes my shoulder. ‘There’s a pub round the corner. Fancy a drink?’

The Golden Harp is quiet and dim-lit. The landlord welcomes Aiden and starts pulling a pint of Guinness. Aiden calls him Jimmy and introduces me as Caoilainn Finnighan, because that’s who I was, am, to him.

When Jimmy learns my name he says, ‘Nothing to do with that cantankerous git up the road, are you?’

‘Christ, Jim, he’s her granddaddy,’ Aiden protests.

‘Sorry, love. I was kidding.’

A ladylike half of Guinness appear on the bar. Aiden collects the drinks and steers me through to the back room. We sit in a corner. He offers me his cigarettes and I take a tentative sip of Guinness. It’s bitter but smooth.

‘Sorry about Jimmy,’ Aiden says. ‘He’s had a few run-ins with your granddaddy.’

I shrug it off. Suffocating silence slides over me. I force myself to break the surface of it. ‘My parents… is that how they died?’

‘It’s how too many folk died.’ Aiden shakes his head. ‘He doesn’t talk about them. Hurts too much, I guess. Something we understand.’

‘We?’

‘Republicans.’

‘And me, how do I understand it?’

‘You wanting that Irish history lesson now?’ he asks.

I study his face, the curling scar. It looks raw, cruel. An accident? A fight? A war wound? I want to feel the pain of it, something to pierce the numbness in my chest. ‘How’d you get that scar?’

He glances around the empty room. In a low voice he says, ‘Couple of UVF lads jumped me. Gave me this too.’ He lifts his sweatshirt, exposing a red, two inch, star-shaped scar in his side. He twists round; the star is mirrored and magnified, wider and redder. I imagine the sharp stabbing of a stitch and know I’m not even close. Alex tried to impress me with a scar once, on his arm. ‘Chicks dig scars, don’t they?’ I rubbed my thumb over the carefully applied oil paint, smearing it. ‘Only if they’re real.’

Aiden’s is real.

‘UVF?’

‘Ulster Volunteer Force. Loyalists.’ He pulls his jumper down.

‘Loyalists?’

‘Aye, loyal to the Crown. Run everything, so they do. We’re after equalling things up but that’ll not happen while the Brits are backing them, so it’s Brits out then a free democratic, thirty-two county socialist republic for everyone.’

My cheek stings with an imagined slap when he says ‘Brits’. I fumble for another cigarette. ‘I thought it was about religion.’

‘They let on it is but God’s nothing to do with it.’

‘So what is it about?’

He sparks my cigarette. ‘It’s about who you are: Irish or British. We’re all Irish on this island but when the Brits bullied Collins into signing the Treaty in ’21 that meant they kept six of Ulster’s counties for themselves they were about saying the people there were British. The Prods kid on it’s true ’cos they think it gives them special status but they get called Paddy on the mainland just the same.’ He smiles at this. ‘Sometimes I wonder the Brits think the Six Counties are worth fighting for but I guess you go hardest over the last crumb, specially when it’s all you’ve left of the mighty British empire. And us, sure, it’s for our homeland we’re fighting: Ireland wholly Irish.’

A movie flashes onto the screen in my brain: a young woman crumpling to the ground, her chest bubbling with blood; a young man falling backwards, a bullet exploding his head.

‘And that’s worth dying for?’ The words burn my tongue. I rinse with Guinness and swallow.

His eyes are fierce. ‘Aye.’

‘And killing for?’

‘It’s not like the papers say. We’re at war.’

‘But innocent people get hurt.’

‘Wise up, that was happening long before we started fighting back. What would you have us do, put up with the discrimination, living in hovels, making do with handouts, being treated like shite? We didn’t start this. Sure, we do our best to keep civilians out of it but if the Brits fight dirty…’ He shakes his head. ‘We’ve got the worst of it.’

I see him in a ditch, lying in wait, gun in his hand. Crawling under a car, depositing a deadly package. Smashing down a door, dragging a stranger from his bed. But the image is reversible. Him in the ditch facedown, gun in someone else’s hand. Him in the car with someone else’s package ticking beneath. Him in the bed; someone else breaking in.

I can picture Aiden like that; he’s safe: alive. Images of him keep me from seeing the bullet-broken young woman, the skull-shattered young man who aren’t.

‘You joined because of your dad?’

‘I volunteered,’ he stresses the word, ‘because things aren’t right, they need fixing.’

‘But he’s involved?’

‘Everyone in the North’s involved, just some folks’re good at kidding on they aren’t. We’re not that daft.’ Aiden studies his Guinness. ‘We’re Republican in our bones. Da’s been in the ’Ra, the Officials, since he was sixteen, like his brothers and their da before. It’s through the ould man we know your granddaddy. We even had a great aunt in the Cumann na mBan, that’s the old women’s division. Alongside Pearse in the GPO for Easter week, so she was. When the Troubles kicked off again the Sticks split. The Provisional IRA came from that. They took over; Da went with them so we moved to Belfast.’

Hearing words familiar from newspapers, I nod.

‘Da slipped the first internment swoop in ’71, when they grabbed a load of poor buggers who’d nothing against them ’cept they were Catholic, but they got him in ’73. We didn’t see him for two years. Our house was raided dozens of times, everything wrecked by squaddies. Ma used to serve tea on newspaper ’cos it wasn’t worth scrounging new plates just for the Brits to break. We’ve been beaten up on the streets, hauled in by the peelers, attacked by Loyalists, all for wanting things fairer; the chance of a decent job, nice house, ya know.’

He doesn’t shout or bang his fists; these are the simple facts of his life. Cold reality ripples through me. They could have, should have, been the facts of my life too. Why the fuck should I’ve been spared it? What gave Daideo the right to excuse me?

‘D’ya mind my brother Connor?’ he continues.

I push down the soured truth, pull faded images towards me: a boy, taller, sharp features, same colouring as Aiden, kicking a football; kicking it towards a smaller boy, fairer, softer, not Aiden.

‘Dark hair, older than you?’

‘Aye, he’s in the Kesh now.’ Seeing my frown he adds, ‘The jail, call it the Maze, so they do, but it’ll always be Long Kesh to us. Danny, born after you left, he’s in the Fianna, that’s for until you’re old enough to be a volunteer.’

‘There was another brother, wasn’t there?’ I see the red-haired boy again, running, cheeks pink, dragging a limp kite.

Aiden draws a shaky breath. ‘Fergus.’ He looks away. ‘Fucking Brits, ’scuse my language, murdered him in Derry two years ago.’

The running boy trips, falls. My memory blacks out. I study the browny snail trails creeping down the inside of my glass. ‘Sorry.’

‘I’m not after upsetting you,’ he adds, ‘but y

ou asked.’

‘It’s just… I don’t… What the hell’m I supposed to do? Yesterday this was a news report, a rally to attend, a petition to sign. Now it’s…’ I go to the window and peer out into the darkness.

‘You’ve to work out what’s important to you,’ Aiden says gently.

‘Oh, that’s all.’ I stay at the window, trying to focus what little light there is, hoping to break through the blackness.

‘You’re important to him,’ Aiden prompts.

Easy for him to believe that.

‘Giving something up’s harder than hanging on to it,’ he adds, filling the blank of my non-response.

‘Why did he send me away?’

‘I guess he didn’t want you involved.’

‘But I am involved. I always was, I just didn’t know it.’

‘You’re best thinking on yourself and your granddaddy.’ Aiden has crept up behind me. ‘That’s why you came back, isn’t it: family?’

Is it?

We drift back to the table. Drink slowly. Aiden asks about college, my art. I picture the unfinished painting of my childhood but it’s too close to some truth I need to hide, so I’m reduced to scouring a receding horizon of shimmering desert mirages for replies.

Back at the bungalow Aiden cooks egg, beans and chips. I sit in the warm bright kitchen as he chops, stirs and fries. Daideo comes when he’s called, lowering himself stiffly into a chair and cramming the food into his slack mouth. I watch as he slops beans down himself. He doesn’t look at me, or say anything. He knocks over the salt cellar. I jump up, open a cupboard, get the dustpan, clear the mess, reach into a second cupboard, get the salt and refill the cellar. As I place it on the table, Daideo catches my wrist. His eyes lock into mine and I realise what I’ve done: I’ve come home.

After tea we sit in front of the box, the jolly compère on the inane quiz show covering our silence. Daideo is in his armchair. As he reaches for his tobacco tin my eyes are drawn to the table, the sketchpad on it. He notices my stare, lifts the pad and, stretching to the bureau on his other side, locks it in a drawer. I tune out the television, trying to catch windblown thoughts.

There’s a life here for me, one that used to be mine. Now it feels like a ring worn on the wrong finger.

Reasons for leaving marshal in my head, overpowering me.

I lie, pinned down by unfamiliar darkness, on the narrow bed that was mine, searching for myself. I can’t be who I am because I’m not who I thought I was. I get up and creep into the lounge.

The bureau drawer is locked but I can feel its weakness. I find a sturdy knife, jam it between lock and frame and twist. The catch snaps. I open the drawer. The sketchpad is on top of a junk muddle. I pluck it out and flip the cover.

The pencil lines on the first page are time-faded. The image is me aged four. I flip through the book, watching myself grow-up, a year a page, noting the ragged tears where sheets have been ripped out, him getting it wrong and starting afresh. There are thirteen ‘me’ in the pad and one blank page. I return to the bedroom, sit at the dressing table and, using his pencils and the dusty mirror, bring the sequence up to date.

The face that stares out from her white-bordered world is an inverted version of me. I hold the pad up to the mirror. See myself.

I can’t be the copy-me now I’ve glimpsed the original. I can’t go back as though there’s nothing here for me when I know there is. Even if that something bloody terrifies me.

I put the pad in the drawer before dawn and head into town. I find the library and make inquiries. The librarian gives me leaflets. Armed with glossy fliers, I catch the return bus, walking in on a one-sided row.

‘It’s your fault, ya bollocks. What the hell were you playing at, getting the lad to fetch her?... Shite, Frank, there’s nothing the matter with me… He’s out looking.’

I clap the door shut. Daideo turns, the phone clamped to his ear.

‘Caoilainn, Jesus sake, where’ve you been? What?... Aye, she’s just walked in. If you’ve an ounce of sense, Frank, you’ll not be showing yourself here for a while.’ Daideo bangs the phone down and faces me. ‘Well?’

I fan the leaflets and hold them like a shield.

‘I can go to college in town, stay with you.’

‘I’ve told you what you’re doing.’ He folds scrawny arms over his chest. ‘You’ll away back where you came from.’

‘Why?’

‘I’ll have no part in you throwing away your future.’

‘How’s me staying here doing that?’

He shuffles into the lounge. I follow.

‘Well?’

He pinches his lips together.

‘This course is just as good. The facilities look excellent.’ I thrust the leaflet under his nose.

He swipes my hand aside.

‘There’s nothing good for you here.’

‘Except you.’

‘Including me.’

‘I’m over eighteen. You can’t make me leave.’

‘But I can tell you you’re not living here.’ He drops into his lazyboy and bangs the chair arm. A cloud of grey dust mushrooms up.

‘Fine. I’ll get digs.’ I walk out, slowly enough for him to call me back. He doesn’t. Shit.

Aiden is hovering in the hall, hair lank with rainwater. I shake my head at him, dart into the bedroom and repack the bag that was only half unpacked last night.

‘What’re you doing?’ he asks, sticking his head through the doorway.

‘Staying.’ I push past him, down the hall and outside.

‘Wait.’

I keep going, up the path, through the gate and along the street. He jogs alongside me a few seconds later.

‘Jesus, Caoilainn,’ he puffs, pressing a hand to his side where the star-shaped scar lurks, catching me with his other hand, trying to slow me down. ‘You can’t…’

‘I can.’ I double my pace. Don’t hesitate. Don’t look back. ‘Know anywhere I can sleep tonight?’

‘Bloody hell. Come on, we’ll ring my da.’

We huddle into the phone box, rain rattling the glass. Aiden explains, listens, says, ‘aye,’ a few times. He holds the receiver to me.

‘Hello?’

‘Caoilainn.’ There’s a gulp or a sob, the drawing of a breath. ‘Aid says you’ve a spot of bother with Pat but don’t worry. We’ll see you OK. ’til the ould fella comes round. It’s grand you came for him. He needs his family.’

His words douse me in doubt. What do I need? What the hell am I doing? Either way it’ll be wrong. ‘Mr O’Neill, I’m not sure I…’

‘It’s Frank, love, and I know it’s a lot you’ve had dropped on you but you being here’s best all round.’

‘Daideo said my parents were killed, shot. That’s more than ‘a lot’.’

A heavy breath in.

‘Sure, ’twas a terrible thing for yous. We were worried it would finish the ould fella.’ His voice is hollow. It brightens again, black and white flicked to colour. ‘But now you’re back things are coming right.’ He hurries on. ‘Sorry, love, there’s someone here. Don’t fret. We’ll look after you.’

With a click he’s gone. I don’t know what it was I hoped he’d say.

We head for the Golden Harp. It’s not 10:30 but Jimmy lets us in. Aiden explains his dad’s plan for Jimmy to put me up at the pub in exchange for me working there. Jimmy and I study each other. From the way he looks at me I see he doesn’t think he has much choice. Neither do I. Or rather, I’ve already made my choice.

Jimmy leads me to a poky room upstairs, brown damp mottling the ceiling, wardrobe with one door hanging off and bed with a mushy mattress. I dump my stuff and head into the bar where Jimmy teaches me to pull a pint. The first two fizz uncontrollably but the third is drinkable. I’m serving on that lunchtime, thankful for the frantic pace that keeps me from thinking about anything other than staying afloat.

After closing I call the landlord of my Plymouth digs, tell him there’s a family crisis; I

’m not coming back. He agrees to send my things if I post a month’s rent in lieu of notice. I agree, hoping I can scrounge the money. I hang up the pay-phone. Is that it? One life ended; another begun? It feels like I should be calling people, making an announcement: Kaylynn Ryan has left herself. But there’s only a handful of familiar faces I nod to in corridors, pitch my easel next to. They wouldn’t care. Nor would the ‘let’s pretend’ parents I don’t want. Nor does the grandfather who doesn’t want me. I slump against the glass door, drained and dizzy. I can’t even cry because there’s no milk spilt.

Later I write to PSAD, withdrawing myself. As the buff envelope slithers into the green letterbox a salty wave drenches me with determination. This needs doing so I’ll bloody well do it.

I muddle through a fortnight, Guinness fumes saturating my clothes, my hands chapped from washing glasses, smile warping into a grimace as yet another punter comments on my accent, cracking jokes about immigrants. I’m a curiosity; the usual form is Irish barmaids leaving for English pubs.

Aiden updates me. His dad keeps phoning Daideo but when he finally walks into the bar, sketchpad under his arm, I know what’s brought him round.

Jimmy nudges me. ‘Catch this,’ he mutters, nodding to where Daideo stands, filling the doorway, glaring at cowering drinkers who avoid the challenge. He faces Daideo. ‘You’re barred.’

‘Fuck off with you,’ Daideo barks, striding over, ‘or I’ll have your bollocks for earrings.’

Jimmy winks at me and wanders away to serve.

‘You’re as stubborn as me, so?’ Daideo says.

‘Apparently.’

‘Lad said you’ve had your things shipped over, given up your college place?’

‘Do you want to see the letter they sent?’

‘I do not.’ Daideo sniffs. ‘Have you found a course here?’

‘Yes, but there’re no scholarships until next year so I’ll be doing this until then.’ I gesture to the beer taps with my dishcloth.

He throws the sketchpad down, open to the last page. ‘I told you I’d have no part in you throwing away your future.’

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain