- Home

- Tracey Iceton

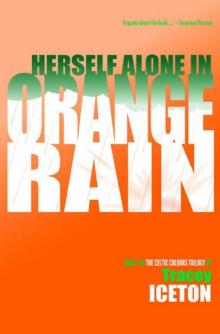

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Page 5

Herself Alone in Orange Rain Read online

Page 5

I scrub a sticky beer ring. ‘Is that you changing your mind?’ I glance from my drawing to him.

He drags a hand over his mouth. ‘I’ll not pretend to like it but you’ve bested me. Jesus, you’re a one,’ he admits. ‘My fault, I know. Now, while you’re under my roof, you’ll live by my rules.’

‘Which are?’

‘Stick in at college, keep out of trouble. No playing nurse for me.’

He is dying, cancer, I guess.

‘Anything else?’

‘No smoking in bed, keep out of my locked drawers and I’ve said my all about the past.’ He holds out a hand so we can shake on the deal. His grip is fierce. I wring his hand like a dishrag.

‘I’ll be round after closing.’

Dublin—18th December, 1980

Maze Seven End Death Fast

Prisoners Ask for Food on 53rd Day

of Hunger Strike

The seven Republican prisoners on hunger strike in the Maze Prison have this morning ended their strike. The decision was made after negotiations between Republicans and British officials. A statement released by the governor of HMP Maze, Mr Stanley Hillditch, announced that the strikers are accepting food and medical treatment. Downing Street has yet to comment on concessions made to Republicans but a Sinn Fein spokesman confirmed that an agreement has been reached in line with the prisoners’ five demands.

The strike began on 27th October after a four year stalemate between IRA prisoners and authorities over demands for political status including; the right to wear their own clothes, have free association, access to recreational and educational facilities and not to do prison work. Similar rights were granted to prisoners under the Special Category status introduced in 1972 for those convicted of political crimes in Northern Ireland. Special Category status was withdrawn in 1976 as part of government counter-insurgency strategies.

The strike was led by Brendan Hughes (32), Officer Commanding (OC) of the Republican prisoners. The other strikers were; Tom McFeeley, Leo Greene, Tommy McKearney, Raymond McCartney, Sean McKenna and John Nixon of the Irish National Liberation Army. They were joined on 1st December by three women Republicans in HMP Armagh; Mairead Farrell (OC), Mairead Nugent and Mary Doyle. They are expected to end their strike today.

Unconfirmed reports yesterday suggested that Mr McKenna had lapsed into a coma. It is believed he is being treated by medical staff at the prison.

We hear of the strike’s collapse on the radio in Daideo’s pokey kitchen as I’m making breakfast. The word, caught on twin currents of steam from the kettle and vapours from the frying pan, splits, the parts drifting away from each other:

break fast

break fast

break fast.

‘You know why they did it?’ Daideo asks.

‘For political status.’ I recite what I’ve learnt so far and spear a sausage. Fat spurts out and drips onto the stove as I lift it to a waiting plate.

‘That’s what they’re doing it for,’ he says. ‘I mean why they do that.’

I put a plate of sausage and egg down. He pushes it away and grips my arm.

‘Sit, Caoilainn, so’s I can tell you.’

‘Tell me after you eat.’ I slide the plate back. His clothes are baggy, his skin ill-fitting. During my two months here he’s wizened. I’m worried. Just as I’m getting better at loving him he’s leaving, vanishing. Soon all that’ll be left will be the granite kernel at his core. It must have filled him once but decades of erosion have left the flesh hanging off him like he’s too big to support himself. A sudden blow will reduce him to ash. Only when I sit does he let go.

‘It’s an ancient Irish practice, from Gaelic law. Troscadh. If somebody wronged you, you fasted on their doorstep ’til they saw you right.’

‘What if they didn’t?’

‘You’d die there for everyone to see. The fella that let you die’d be shamed, an outcast.’

‘What if you change your mind, go home and stick a fry on?’

‘You don’t.’ His eyes burn through me.

He’s teaching me; a folk song, a superstition, Gaelic words: Irish essence. Energy blazes in the watery blue, shining against bloodshot whites as he tutors. He’s read me the Táin so many times I dream the Cúchulainn legends. I like the stories of Queen Medb and Scáthach best, women of power and knowledge, women with control: women who fight. They get on well with George, the fierce little girl from the Famous Five adventures who is the solitary hero from my real childhood. Her cry, ‘I’m as good as any boy,’ could have come from their lips.

But not all his lessons slot comfortably into the past I’ve grown up with. The bedraggled British Tommy, floundering in the Flanders’ trenches becomes Black and Tan butcher hunting Irish Volunteers through the Cork countryside once I’ve learnt my Irish history. At least, Daideo’s version of it, which ends in 1937 with the renaming of the Irish Free State as Eire in de Valera’s 32-county constitution, Dev’s way of writing partition out of Ireland’s story. 1937 was also the year Cathal Finnighan was born, according to my birth certificate, a wound I daren’t touch, no matter how much I might want to, for fear of making it haemorrhage again, fatally this time. Of Daideo’s history I have only Aiden’s IRA legend: the boy who fought for Pearse, then Collins, then Dev, then whoever was left. Time is rubbing my chance of hearing it from the hero’s mouth into smaller and smaller grains.

‘Finish your breakfast, Daideo. I’ve a class.’

He lifts a fork. ‘When am I going to see your work?’

‘You’ve seen plenty.’

‘Those wee sketches! I’d done half a dozen grand oils before I was your age.’

‘And I’ve not seen one of them,’ I remark, shrugging on my coat.

‘You can thank the Auxies for that, razing the land from Wicklow to Galway,’ he mumbles.

When I return from college, a small canvas of the Wicklow mountains in my bag, he’s in the hall, wearing his hat and coat.

‘We’re off out.’

‘Where to?’

‘The past, if it’s still there,’ he chunters, taking his stick from the hall stand.

We catch a bus towards Rathfarnham and get off in a quiet street. Neat houses line the pavement and bare-limbed trees stretch overhead. Daideo strides out. I jog to catch up.

‘Where’re we going?’ I repeat. He’s said nothing since we set off, keeping his lips pressed into a hard line, his eyes on the scrolling view through the bus window.

‘You’ll see.’

We round a bend in the road and track along a high stone wall. A few yards on the wall is broken by two sets of wrought iron gates, the first wide enough for vehicles, the second person-sized. The smaller gate is set into a stone entrance, arched around the gate, squared off above and topped with a reclining beast that could be a lion or something more mythical. Gold letters proclaim it the ‘Pearse Museum’.

‘Didn’t say that in my day,’ he mutters, passing under the arch. ‘Keep up, lass.’

I trot after him.

He slows down further along the sweeping drive, stopping to peer into the undergrowth or across the lawns, seeing things invisible to me. We reach a blind corner. He halts, looking back the way we’ve come, removing his hat as for a funeral procession. His hand trembles.

‘What’s wrong, Daideo?’

‘It’s been too long and not long enough.’ He replaces his hat and presses on.

A building, so large and grey it could have been hewed from solid rock, rises in front of us. Steps lead to a columned entrance and three rows of windows reflect the day’s dull sky. Above the entrance are the words ‘Músaem na Ó Píarsach’. Daideo points.

‘What’s that say?’

‘The Pearse Museum.’

‘Are you guessing or did you read it?’

‘A bit of both?’

He sighs. ‘Do you know where we are?’

‘Yes.’ I point to the engraving. ‘The-Pearse-Museum. Patrick Pearse.’

‘Aye, and his brother Willie. He doesn’t get forgotten by me.’ Daideo shakes his head. ‘A bloody museum! There should be boys playing on these fields, sitting behind those windows, learning and laughing.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘This is, was, St Enda’s. The Pearses’ school.’

‘Aiden said you knew him.’

Knowing Pearse, being with him in ’16, fighting at the General Post Office during Easter week, it’s Republican grail.

‘He didn’t hear that from me.’

‘It’s not true?’

Daideo faces me. ‘I knew them all; the Pearse clan, Sean MacDermott, Joe Plunkett, Con Colbert, Tom MacDonagh, James Connolly, Madam Markievicz, Tom Clarke, Mrs Clarke, Eamonn Kent, Mick Collins, The O’Reilly.’ He recites their names reverently then climbs the steps, looks through the window, tries the door.

I notice a sign.

‘The entrance is round the side, Daideo.’ I wave him down from the portico but he sits on the top step, beckoning me. I perch beside him, worrying he’ll catch a chill from the stone’s radiating cold.

‘It’s more than sixty-five years since I was here, nearer seventy since I first came up that drive. I was twelve years old, miles from home and bloody terrified. Now I’m a canny bit older, two miles from home and…’ He presses his fingers into his eye sockets. ‘Jesus, it’s still too soon for me to come back. Give me a cigarette for Christ sake.’

I fish in my pocket. ‘You shouldn’t at your age.’

He snorts. ‘It’s you that shouldn’t.’

We sit smoking, our arses numbing, then head for the entrance. Daideo counts the money for two concessions and remarks on the price being cheaper than when he came as a boarder. The curator asks was he a St Enda’s boy?

‘I was.’

The entry fee is waived.

Guided by the curator, we meander through the refurbished Edwardian interior, along passageways with tan-polished parquet floors and high white ceilings. Light fittings with shades fluted like lilies hang in the rooms. Mahogany dressers line the corridors, displaying books and teaching resources. We enter the study hall, politely admiring its raised stage, leaf-green walls and recessed chapel. The curator crosses himself as we draw towards the altar. Daideo scowls and mutters curses. We trespass into family rooms filled with personal items; a sideboard draped with a lace doily, a kneeling statuette, an elegantly carved harp, two over-sized teacups displayed like trophies in a glass cabinet. It’s the teacups that Daideo pauses reverently before. The curator leads us to classrooms, now housing information boards instead of blackboards and display cases, not desks. He asks Daideo for memories; which rooms for which lessons, which masters taught there in his day? We stroll between two rows of beds, complete with counterpanes and crisp pillowcases, in a remade dorm. Does sir recall which bed was his, who he bunked with? He’s fishing, but daren’t ask: was sir there before Easter 1916? Daideo doesn’t bite.

We come to the headmaster’s office, Pearse’s sanctum, and crowd behind the rope protecting this hallowed ground; only the worthy may enter. I try picturing Daideo as a boy, here getting a bollocking from Pearse, but it’s too much an Enid Blyton children’s story to be real for me.

Daideo listens to the curator’s patter about Pearse’s books, the family portraits, the seat in which he sat, they say, to pen the proclamation.

‘And a few drafts it took him. There was paper strewn all over the night he was finishing it.’ Daideo gestures round the room.

The curator fluffs his next line and before he recovers, Daideo has unhooked the rope and crossed the office to where a framed photograph hangs above a bureau.

‘Sir, you mustn’t…’

Daideo ignores him. ‘Caoilainn, come here.’

With a shrug to the curator I join him beneath the photo. It shows the school turned inside out; building, masters and pupils assembled on the drive in front. Daideo presses a finger to the glass.

‘There’s your man, Pearse.’ He moves his finger along. ‘Willie.’ Up to the rows behind. ‘Mr Plunkett, Mr Colbert, Mr Slattery.’ He draws the finger sideways, to the face of a boy, about fifteen, fair curls that look pinkish in the sepia-tinted print. ‘And me.’ He rounds on the curator. ‘What happened to the paintings that were here, ‘Íosagán’?’ Daideo lurches at him. I lay a hand on his arm.

The curator’s nostrils flare. ‘There wasn’t room,’ he stutters. ‘They’re in storage.’

‘Show me.’ The words are barked.

The curator takes us to the basement. Stale air escapes as the heavy door creaks open. Leaking pipes drip-drip. A misshapen mountain rises, dustsheet-draped, corners jutting, suggestive of boxes.

‘That’s all of it,’ he mumbles, shuffling off.

Daideo rips the sheets aside and begins flinging boxes with mythical strength.

‘Are you not going to help?’

In twenty minutes we’ve moved the mountain, unearthing canvasses tied into an oversized package. With his pocket knife Daideo snaps the twine. We shake off the covering and he squats in front of the first painting.

‘No.’ He slides it to me. ‘Take it, lass.’ Studies the next while I move it.

I’ve shifted five when he gives a stunted cry.

‘What’s wrong?’ I dart to his side.

He’s frozen, one hand clutching a painting, a four by three of the building we’re in, the other crammed into his mouth. He pulls the canvas free and props it against the wall, face to the chalky brickwork.

‘We’ll take that.’

‘We can’t.’

‘We can. It’s mine.’ He starts in on the stack again but stops abruptly. ‘And this one.’ He takes the second painting over to wait with the first before riffling through the remainder. ‘But where’s ‘Íosagán’?’

‘What are you looking for?’

‘The painting that hung in the entrance.’ He reaches the second but last of the stored pieces. ‘Jesus, it’s here.’

It’s of a boy standing between two trees, fair-haired, bare-chested, a cloth wrapped around his waist, falling to his naked feet. A golden halo encircles his head. His arms are outstretched, making a cross of his lithe body. Daideo hands the canvas to me and I wait while he rewraps the two he’s claimed as his own.

We lug all three up to where the curator is waiting near the entrance/exit.

‘This,’ Daideo points at the one I’m holding, ‘needs to be hung in the entrance hall.’ He nods to me and I press it onto the curator. ‘These others are mine. I’ll be taking them, so I will.’

‘You will not,’ the curator splutters.

‘You gonna stop me, wee fella?’ Daideo draws himself up, sagging muscles tensing, bloodshot eyes blazing.

The curator withers. ‘I’ll be telephoning the police.’

‘Grand. Been a good while since I walloped a rozzer,’ Daideo says as he humps the parcel onto his shoulders.

Back home, barricaded inside, I make tea while Daideo unwraps the paintings in the front room. When I enter with the tray he has them propped by the fire. I put the tray down and study them.

The painting of the school is impressive in its detail, the brickwork, the window frames, and captivating in the unusual colour scheme. The sky is dawning gold, white and green; the grounds burn redly. A cluster of lilies are planted bottom left.

In the other painting I recognise the boy-warrior, Cúchulainn. The young hero waits, spear raised, among vast hills, under tumultuous cloud banks, hordes of enemy soldiers gushing down the valley towards him.

I drop onto my knees, admiring the fat brush-swirls of sky and earth, the fine lines and tiny dots that make up men and masonry.

‘What do you think?’ Daideo demands.

His artist’s pride is the key to his past.

‘Tell me about boy who painted them, then I’ll say.’

I sit on the sofa opposite the paintings, trying to superimpose Daideo onto the young boy who was first William, then Finn Devoy, then Patrick Wil

liam Finnighan; innocent, hero, outlaw. The rucksack he fetched from the attic is on the seat beside me. I pinch age-stiffened leather, trace the letters ‘PWF’ scored with a penknife into the brown hide. PWF: Patrick William Finnighan, the name he gave himself when he’d outgrown Finn Devoy, borrowing first and middle from the Pearse brothers who once carried that haversack over Connemara’s hills. The surname he made up, salvaging what was left of himself when he took the bag and set out on foot, heading for the future. The three names make a total less than the sum of the parts.

Inside the bag is Daideo’s life: a photograph of his junior hurling team; another showing two boys dressed as Gaelic warriors; a battered copy of the Táin inscribed with birthday greetings and signed ‘Cathleen’; a similarly tattered Bible with a mother’s love on the flyleaf and a bullet wound in its chest. There’s ‘Finn’s’ long-expired American passport; the bullet dug from his shoulder in 1920; a brittle copy of his wanted poster from ’22; a matchstick model made in the Curragh sometime between ’31-4; a lock of his son’s fair hair; the engagement announcement of Cathal Finnighan and Fiona O’Shea; a tiny wrist tag in the name of Caoilainn Patricia Finnighan.

It bundles me into my own past, the dead parents I’ve gained and the living ones I’ve discarded. Two mothers, two fathers, all putting their fights, their causes, before me. I can get the why but the ‘how could they?’ is still hard to fathom.

A tap on the window drags me into the present. I peek behind the curtain. Aiden’s face is pressed against the glass. His visits are irregular, dictated by Army business.

‘How are ya?’ he whispers as he slips in.

‘Fine. You want tea?’

‘Aye. He’s asleep?’

‘Yeah, go through.’

When I return with two mugs Aiden is admiring the paintings.

‘When did you do these?’

‘I didn’t. They’re his.’

I confess our art heist. He chuckles when I repeat Daideo’s remark about walloping a rozzer, is sombre when I recount Daideo’s autobiography.

Herself Alone in Orange Rain

Herself Alone in Orange Rain